A Financial Review of Autism Services and Program Design Considerations for the New Ontario Autism Program

1 | Summary

Overview and Background

- Autism spectrum disorder (autism) is a lifelong neurological disorder that can affect a person’s behaviour, social interactions and ability to communicate. The FAO estimates that there are about 42,000 children and youth living with autism in Ontario. Families with children on the autism spectrum often seek behavioural therapy programs to improve language, communication and social skills, which can cost up to $95,000 per year depending on the individual needs of the child.

- Families with children on the autism spectrum can apply for support from the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services (MCCSS), which provides a number of different services. Since the introduction of the first autism support service in 1999, the Province has made a number of changes to its programs, including:

- In 2011, needs-based behavioural therapy services were offered in separate intensive behavioural intervention (IBI) and applied behavioural analysis (ABA) programs, each with their own waitlist.

- In 2017, the Province introduced the Ontario Autism Program (OAP), which merged autism therapy services and increased funding to address the growing integrated waitlist.

- In 2019, the Province announced that it would reform its autism programs by replacing the OAP with age-based Childhood Budgets and committed to eliminate the waitlist entirely. However, the Province cancelled this reform later in 2019 and announced that it would introduce a new needs-based OAP by 2021.

- As of July 2020, Ontario’s main programs to support children on the autism spectrum are in a stage of transition. Children currently receive support through:

- the old OAP, which delivers needs-based behavioural therapy services;

- Childhood Budgets, which provide families with children under the age of six with $20,000 per child per year and families with children age six and older with $5,000 per child per year, to procure their own services;[1] or

- interim one-time funding, which provides a payment to families similar to Childhood Budgets.

Autism Services Spending

- From 2004-05 to 2019-20, the Province’s annual spending on autism services grew from $67 million to $608 million, a nearly ten-fold increase. More recently, from 2015-16 to 2019-20, total spending on autism services grew at an average annual rate of 34 per cent due to the creation and expansion of the OAP, beginning in 2017, and then the introduction of Childhood Budgets in 2019.

- Of the $608 million in total autism services spending in 2019-20, the Province recorded unaudited spending of $271 million for needs-based services, $270 million for Childhood Budgets and interim one-time funding, and $67 million for other services.

- The $270 million in spending for Childhood Budgets and interim one-time funding includes $97 million for 8,100 children whose families received payments in the 2019-20 fiscal year and an accrued expense[2] of $174 million for 25,100 children whose families did not receive payments by March 31, 2020, the end of the fiscal year.[3] MPPs should confirm with the Auditor General of Ontario that the Province can record the full accrued expense of $174 million as spending in 2019-20.

Waitlist for Needs-based Autism Services

- The waitlist for the ministry’s needs-based children’s autism services, such as behavioural therapy programs, has grown significantly since 2004-05. Between 2004-05 and 2011-12, the waitlist grew at an average annual rate of 22.9 per cent. Starting in 2011-12, the Province expanded the eligibility for autism supports, which drove an even greater demand for services. From 2011-12 to 2018-19, the waitlist grew at an average annual rate of 47.8 per cent, from 1,600 children in 2011-12 to 24,900 in 2018-19.

- In 2019-20, the waitlist for needs-based services grew to about 27,600 as the ministry stopped enrolling children into needs-based services under the OAP. Instead, the Province offered families funding in the form of Childhood Budgets and interim one-time funding.[4]

Spending per Client under Different Support Programs

- Since 2011, the Province has offered three distinct autism programs: IBI/ABA programs (from 2011 to 2017), the OAP (from 2017 to 2019) and Childhood Budgets (2019 and 2020). Each of the three support programs had different budgets, design and objectives, which resulted in different average costs per client. In today’s dollars, the FAO estimates that the average annual cost per client for the IBI/ABA programs was $19,800, the average cost per client under the OAP was $29,900 and the average cost per client for Childhood Budgets was $8,100.

The New OAP: Program Design Considerations

- The Province has committed to a new needs-based Ontario Autism Program by 2021 with an annual budget of $600 million. The new OAP is currently under design, with a working group providing advice on the implementation of the new program, including service levels (length of service and intensity) for needs-based support. One of the Province’s stated objectives with the new OAP is to move a minimum of 8,000 children off the waitlist into needs-based services in the first full year of the new program.

- To support MPPs’ review of the new OAP, the FAO developed program design scenarios with the following variables: budget, service level, number of clients served and waitlist.

Scenario 1: Fixed Budget and 2019 OAP Service Level

- With a fixed annual program budget of $600 million and a needs-based service level similar to the level of support provided by the OAP in 2018 and 2019 ($29,900 per client), the FAO projects that 17,860 children would be able to access needs-based services under the new OAP.

- Compared to the 2019-20 average, an additional 8,700 children would receive needs-based support each year under the new OAP. On the other hand, the FAO projects that the waitlist for needs-based services would be 22,900, a reduction of 4,800 from the waitlist in 2019-20, due to the projected increase in caseload by 2021.

- Under this scenario, over half of the children and youth registered for needs-based autism services (56 per cent) would be on the waitlist. This would be an improvement from 2018-19 (71 per cent of registered children on the waitlist) and 2019-20 (75 per cent of registered children on the waitlist).

Scenario 2: Fixed Budget and Lower Service Levels

- With a fixed $600 million annual budget, lowering service levels would allow the Province to increase the number of children that receive needs-based support and reduce the waitlist.

- Based on the FAO’s analysis, in order to completely eliminate the waitlist for needs-based services, the average cost per client would need to be reduced to $13,100. This would result in a significant reduction in the average level of needs-based support available per child. Compared to service levels under the OAP in 2018 and 2019, service levels in this scenario would be reduced by approximately 56 per cent.

- Alternatively, if the new OAP were to provide service levels similar to the IBI/ABA programs offered prior to 2017, at an average cost per child of $19,800 (in today’s dollars), then the waitlist would be reduced to 13,800. This would equate to a service level reduction compared to the 2018 and 2019 OAP of approximately one-third.

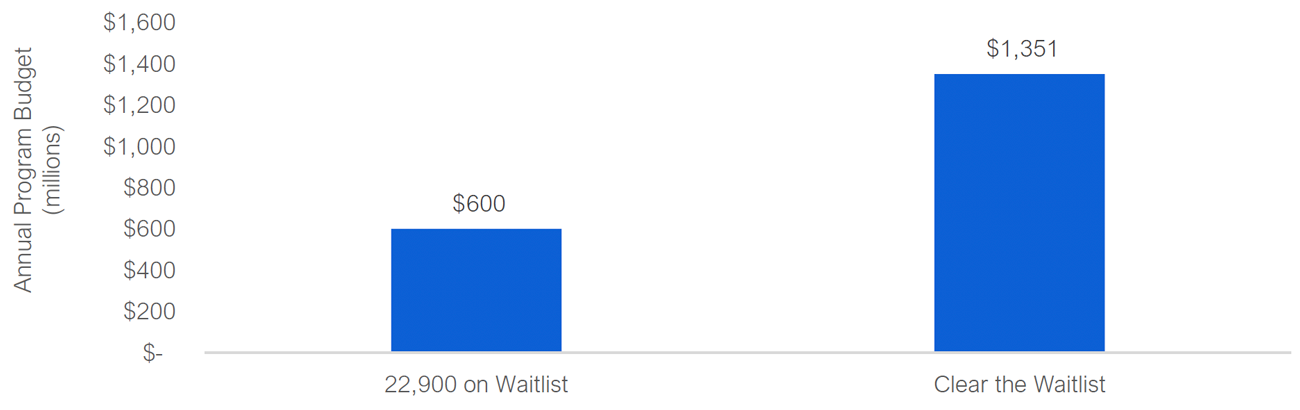

Scenario 3: Increased Budget and 2019 OAP Service Level

- In this scenario, the FAO maintained the needs-based service level from the 2018 and 2019 OAP, with average spending of $29,900 per child, and estimated the budget required to clear the waitlist.

- To eliminate the waitlist entirely, the annual budget for the new OAP would more than double to $1.4 billion. This would result in approximately 40,700 children and youth receiving needs-based services with an average cost of $29,900 per child.

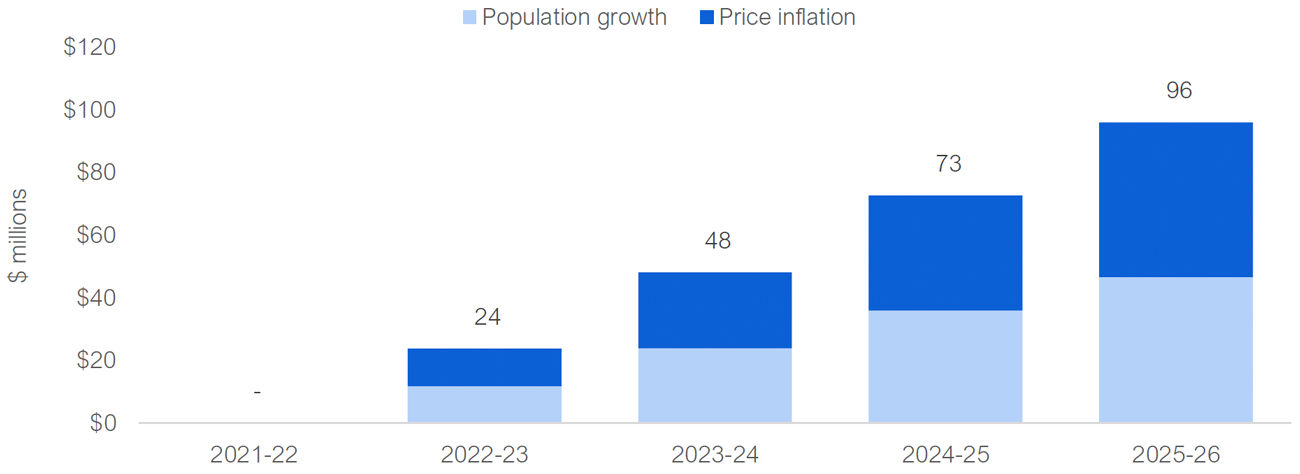

Other Considerations: Cost Pressures and Staff Availability

- The government has not indicated whether the $600 million annual budget for the new OAP will increase over time. Assuming that the autism prevalence rate remains stable at approximately 15 out of every 1,000 children and youth under the age of 18, population growth will add a cumulative total of 1,600 children and youth registered for needs-based support by 2025-26. Over the next five years, price inflation is expected to average two per cent.

- The FAO estimates that to maintain the new OAP’s service levels and to ensure that the waitlist does not increase, the Province would need to increase the OAP’s annual budget by $96 million to $696 million by 2025-26.

- In addition to cost pressures, there is a risk that the delivery of the OAP could be constrained by the supply of needs-based therapeutic services for children and youth on the autism spectrum. As the Province expands needs-based services to more children, it will need a sufficient availability of qualified behavioural clinicians, speech language pathologists and occupational therapists to provide needs-based services.[5]

- The FAO questioned the ministry on the supply of qualified behavioural clinicians, speech language pathologists and occupational therapists necessary to accommodate the expansion of needs-based services under the new OAP. The ministry responded that limited information was available on the autism services labour market and that the ministry was in the process of collecting information to confirm the availability of qualified clinicians needed to meet demand under the new OAP.

2 | Introduction and Background

Overview of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism spectrum disorder (autism) is a lifelong neurological disorder that can affect a person’s behaviour, social interactions and ability to communicate.[6] For example, people on the autism spectrum may have challenges sustaining conversations, understanding or using nonverbal communication (such as eye contact or facial expressions) and communicating verbally.[7] As a spectrum disorder, autism affects people differently and symptoms range from mild to severe. Mild symptoms include minor challenges with communication and social interaction. More severe conditions include serious cognitive disability, sensory problems and symptoms of extremely repetitive behaviour.[8]

Based on a national study on the prevalence of autism in Canada, about 15 out of every 1,000 children and youth under the age of 18 live with autism.[9] Based on this rate, the FAO estimates that there are about 42,000 children and youth living with autism in Ontario. While autism can be diagnosed before two years of age in some children, the Auditor General of Ontario reported that the median age at which children receive a formal diagnosis in Ontario is just over three years old.[10]

Autism Support in Ontario

Families with children on the autism spectrum often seek behavioural therapy programs to improve language, communication and social skills. Autism therapy can be very expensive – costing up to $95,000 a year[11] – and varies depending on the individual needs of the child, the number of hours per week of service and the duration of the services provided.[12] Families with children on the autism spectrum can apply for support from the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services (MCCSS), which provides a number of different services. The main supports delivered through MCCSS are behavioural therapy services and annual budgets through which families can independently purchase services.

The Province’s behavioural therapy services include both applied behavioural analysis (ABA) therapy services and intensive behavioural intervention (IBI) therapy services. ABA typically lasts two to four hours per week for two to six months.[13] In contrast, IBI is generally provided to children on the severe end of the autism spectrum, for up to 20 to 40 hours a week and can last for several years. IBI is delivered by a trained professional one-on-one or in a small group, whereas ABA techniques can be used by caregivers at home and at school.

Other services provided by MCCSS include support for the learning needs of children transitioning into school, autism diagnostic assessments, providing families with a support worker to help navigate the ministry’s autism support services, and funding for families to recruit a respite care worker to provide short-term relief caring for their children and youth on the autism spectrum.[14]

Waitlist for Needs-based Autism Services

The waitlist for the ministry’s needs-based children’s autism services, such as behavioural therapy programs, has grown significantly since 2004-05. Between 2004-05 and 2011-12, the waitlist grew at an average annual rate of 22.9 per cent. Starting in 2011-12, the Province expanded the eligibility for autism supports, which drove an even greater demand for services. From 2011-12 to 2018-19, the waitlist grew at an average annual rate of 47.8 per cent, from 1,600 in 2011-12 to 24,900 in 2018-19.[15]

In 2019-20, the waitlist for needs-based services grew to about 27,600 children as the ministry stopped enrolling children into needs-based services under the Ontario Autism Program (OAP). Instead, the Province offered families funding in the form of Childhood Budgets and interim one-time funding while they waited for the Province to implement a new needs-based autism program under a revised OAP.[16]

Figure 1: Waitlist for children’s needs-based autism services, 2004-05 to 2019-20

Note: 2004-05 to 2011-12 represents the waitlist for IBI services, 2012-13 to 2016-17 represents the waitlist for ABA services, and 2017-18 to 2018-19 represents the OAP waitlist. The 2019-20 waitlist includes 8,100 children who received Childhood Budgets or interim one-time funding.

Source: FAO analysis of data from the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

Recent Autism Program Changes

The Province has made many recent changes to its autism services. Originally, behavioural therapy services were split into separate IBI and ABA programs, each with their own waitlist. The full implementation of the OAP in 2018 merged autism therapy services and increased funding to address the growing integrated waitlist.

In 2019, the government announced that it would reform its autism programs by replacing the OAP with Childhood Budgets and committed to eliminate the waitlist entirely. However, the government cancelled this reform later in 2019 and announced that it would introduce a new needs-based OAP by 2021.

As of July 2020, Ontario’s main programs to support children on the autism spectrum are in a stage of transition. Children currently receive support through:

- the old OAP, which delivers needs-based behavioural therapy;

- Childhood Budgets, which provide families with children under the age of six with $20,000 per child per year and families with children age six and older with $5,000 per child per year, to procure their own services;[17] or

- interim one-time funding, which provides a payment to families similar to Childhood Budgets.

Purpose of this Report

The purpose of this report is to provide Members of Provincial Parliament (MPPs) with information on the Province’s autism services and program design considerations for the new OAP, which is scheduled to be in place by 2021. In chapter 3, the report begins with an historical overview of autism services and spending. This chapter reviews changes to autism services, identifies funding levels, and discusses the number of clients served and spending per client under the various programs. In chapter 4, the FAO provides program design considerations for the new OAP by estimating the impact to the waitlist, service levels and program budget under different scenarios.

This report focuses on autism services for children and youth within the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services. Autism services administered by other ministries, such as the Ministry of Education, are outside of the scope of this report.

Appendix A provides more information on the development of this report.

3 | Autism Services and Spending to 2019-20

Overview

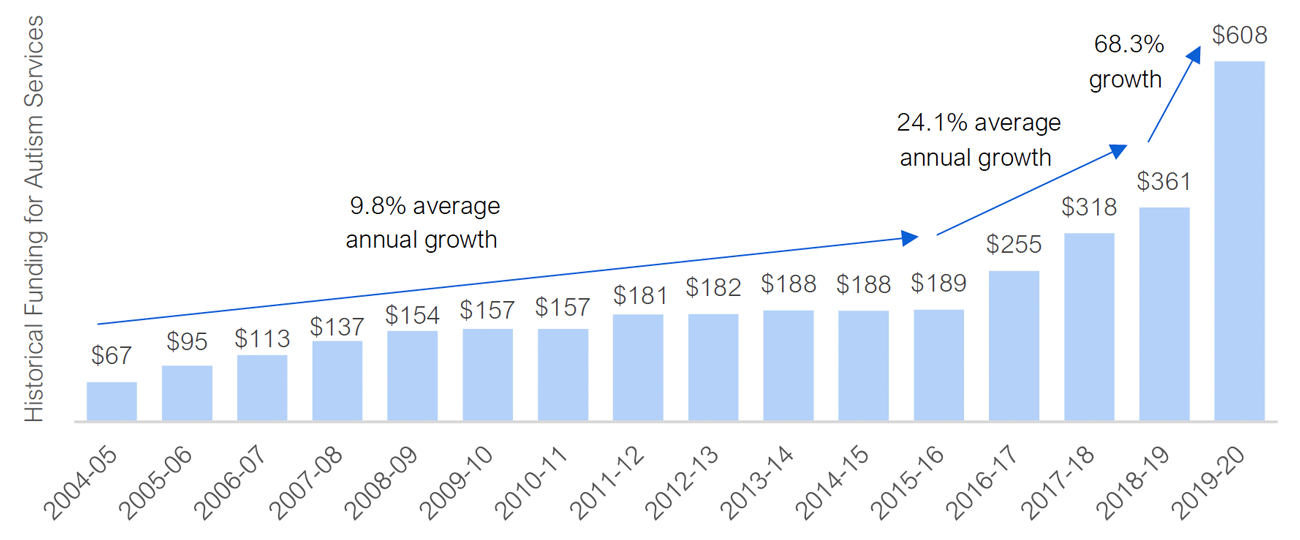

Since the introduction of Ontario’s autism programs in 1999, the Province’s spending on autism services has increased significantly. In 2004-05, the Province spent $67 million supporting children on the autism spectrum, growing to $189 million by 2015-16. From 2015-16 to 2018-19, funding for autism services increased at an average annual rate of 24.1 per cent to $361 million as the Province introduced the Ontario Autism Program (OAP), which expanded access to behavioural therapy and other services. In 2019-20, with the introduction of Childhood Budgets, autism spending reached $608 million, a nearly ten-fold increase from 2004 spending levels.

Figure 2: Historical funding for autism services (millions)

Source: The Public Accounts of Ontario and FAO analysis of information provided by the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

History of Ontario Autism Services

Autism Services prior to 2017

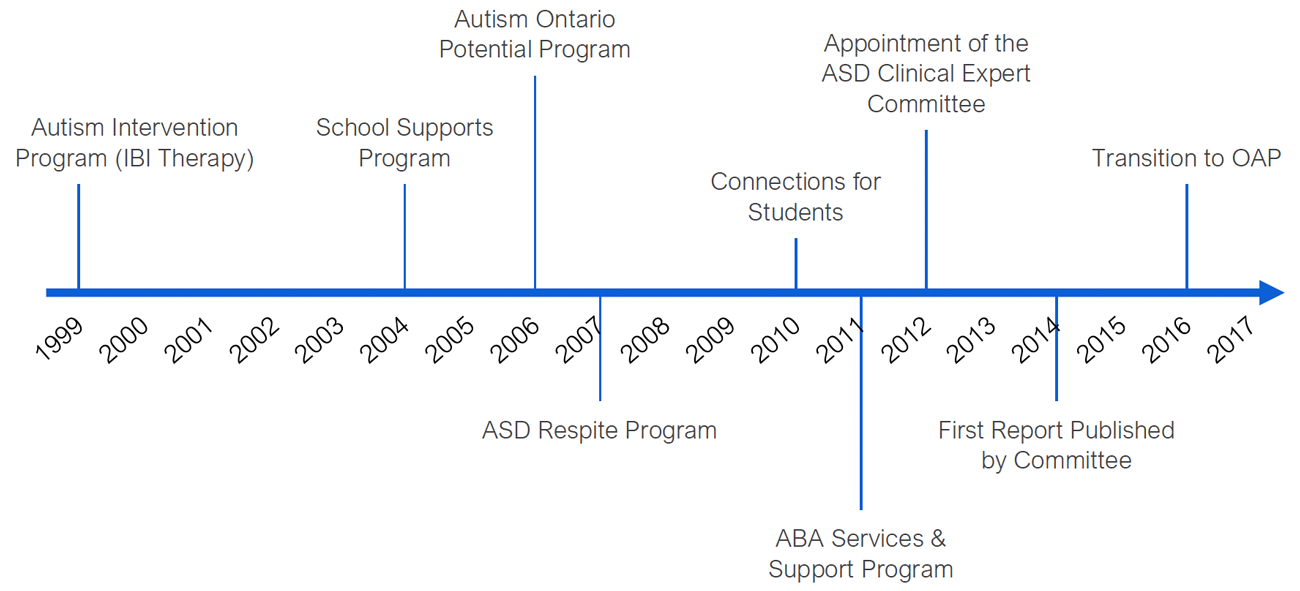

In 1999, the Province introduced the Autism Intervention Program (AIP), which provided $5 million in funding for intensive behavioural intervention (IBI) services for children on the severe end of the autism spectrum. Initially, the AIP was only available to children six years of age or under; however, the Province removed the age cut-off following a court challenge from parents of children on the autism spectrum. In 2004, the Province created the School Support Program to provide training to educators on how to support students on the autism spectrum. Between 2006 and 2008, the Province introduced two new programs to support families of children on the autism spectrum. The Autism Ontario Potential Program supplied families with resources, training, family networking and social learning opportunities for their children. The Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Respite Program provided families with in-home and out-of-home respite opportunities as well as access to seasonal camps. In 2010, the Province created the Connections for Students program, to help transition children receiving autism services into a school environment.

In 2011, Ontario expanded autism services by introducing an applied behavioural analysis (ABA) program. Unlike IBI services, which were available for children on the severe end of the autism spectrum and initially limited to children under the age of six, all children and youth with a diagnosis of autism were eligible for ABA services. The creation of the ABA program with broadened eligibility criteria drove a rapid increase in demand for services. By 2012, the government was spending an average of $17,100 on behavioural therapy services per client.[18]

In 2012, the Province appointed the Autism Spectrum Disorder Clinical Expert Committee to provide guidelines for clinical decision making and benchmarks to ensure that children on the autism spectrum received effective, evidence-based intervention.[19] The Committee published its first report in 2014, which recommended targeting IBI services to children aged two to four years old, expanding ABA services and providing better coordination of autism services between community-based programs and schools.[20]

Figure 3: Historical autism services, 1999 to 2017

Source: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

Ontario Autism Program, 2017 to 2019

In the 2016 Ontario Budget, the Province announced $333 million over five years for a new Ontario Autism Program (OAP) that would begin in June 2018.[21] This funding was in addition to the approximately $190 million annual budget for autism services. The goals of the OAP were to provide integrated autism services,[22] reduce wait times and expand access to ABA therapy.

Initially, the OAP limited IBI services to children aged two to four. Children five years and older who were waiting for IBI services were to be transitioned out of the IBI waitlist through a one-time payment of $8,000 to directly purchase services. In June 2016, the Province announced further changes to the OAP and an additional $200 million over the following four years to support several new measures.[23] Under the updated program, IBI services would no longer have an age cut-off. Families previously transitioned off the existing IBI waitlist would have the option to receive ongoing payments of $10,000 or access to ABA services until their children received services through the OAP.[24] The updated OAP was also scheduled to begin a year earlier in June 2017.

When the OAP was fully implemented, the average spending per client had increased significantly to approximately $29,900 per client due to an expansion of services. This included:

- an increase in capacity for IBI services to accommodate children over the age of four who had previously been ineligible;

- the introduction of a new direct funding option in January 2018, giving all families a choice of receiving therapy services from a ministry-funded provider or receiving funding to purchase services from a private provider of their choice; and

- an increase in the maximum hourly rate for behavioural therapy services purchased through the direct funding option from a maximum of $39 per hour to $55 per hour.

In addition, as part of the implementation of the OAP, five new regional diagnostic hubs were created, 45 new Family Support Coordinators were introduced and funding support for children on the autism spectrum in public schools was increased.[25]

Childhood Budgets and Interim One-time Funding, 2019 to 2020

In February 2019, the Province announced that it would reform the OAP, effective April 1, 2019, to eliminate the waitlist for autism services. Under the new program, all eligible families would receive a “Childhood Budget” to fund autism services for their children. The new Childhood Budgets would provide funding based on family income and child age, rather than the individual needs of the child as per the OAP.[26] Children under the age of six would be eligible for up to $20,000 per year and children aged six and older would be eligible for up to $5,000 per year, depending on family income level.

In March 2019, the government introduced changes to its new Childhood Budgets program. The Province doubled the annual program budget to $600 million, eliminated income-testing for Childhood Budgets and, for those children who were already receiving needs-based services, allowed a one-time,[27] six-month renewal of therapy services.[28]

Finally, on April 2, 2019, the Province announced that it would reconsider its recent changes to autism services and would consult with families and other stakeholders on a new needs-based program.[29] In December 2019, the Province also committed to provide all families on the waitlist for needs-based support, who had not yet received their Childhood Budgets, with an invitation for interim one-time funding of $5,000 or $20,000, depending on the age of the child.[30]

Spending on Autism Services, 2015-16 to 2019-20

Autism services can be grouped into four main categories: needs-based services, transitional funding, Childhood Budgets[31] and other services. Since 2015-16, the largest spending category has been needs-based services, which included historical IBI and ABA therapy programs to 2017-18 and the OAP from 2017-18 to 2019-20. Transitional funding in 2016-17 and 2017-18 provided payments so that families removed from the IBI waitlist could purchase therapy services until their children were enrolled in the OAP. Childhood Budgets in 2019-20 also provided payments to families to purchase autism services. Other services includes respite services, school supports for students on the autism spectrum, diagnostic hubs and other programs.

Figure 4: Spending on Ontario autism services by category (millions)

Note: Childhood Budgets includes interim one-time funding.

Source: FAO analysis of data from the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

From 2015-16 to 2019-20, total spending on autism services grew at an average annual rate of 34 per cent due to the creation and expansion of the OAP, beginning in 2017, and then the introduction of Childhood Budgets in 2019. In 2015-16, the Province spent a total of $189 million on autism services, of which $148 million was for needs-based services and $41 million was for other services.

In 2016-17, autism services spending grew to $255 million, of which $170 million was for the needs-based IBI and ABA programs. Additionally, as the Province prepared to switch to the OAP, it spent $37 million in 2016-17 on transitional payments, which provided families removed from the IBI waitlist with $8,000 and then additional $10,000 payments until their children were enrolled in the OAP.

In 2017-18, the Province spent a total of $318 million on autism services, an increase of $63 million from 2016-17. Spending on transitional payments totalled $67 million, an increase of $29 million from the prior year, while spending on needs-based services totalled $199 million.

In 2018-19, the Province began the year with a budget for autism programs of $321 million but finished the year spending $361 million.[32] The additional $40 million in spending was the result of more families choosing a higher-cost needs-based service option and also more needs-based service hours being billed at the maximum allowable cost per hour.[33] Overall, spending on needs-based services reached $317 million in 2018-19, an increase of $118 million from 2017-18. This increase was partially offset by the end of transitional payments, which totalled $67 million in 2017-18.

In 2019-20, the Province began the year with a budget for autism services of $331 million but finished the year recording unaudited spending of $608 million.[34] Autism services spending increased by $277 million from the 2019 budget plan as a result of the decisions to allow those children who were already receiving needs-based services a renewal of therapy services for up to 12 months (two six-month extensions), to eliminate the income-test requirement for Childhood Budgets, and to make interim one-time funding payments.

Of the $608 million in total autism services spending in 2019-20, the Province recorded spending of $271 million for needs-based services, $270 million for Childhood Budgets and interim one-time funding, and $67 million for other services. The ministry reports that the $270 million in spending for Childhood Budgets and interim one-time funding included $97 million for 8,100 children whose families received payments in the 2019-20 fiscal year and an accrued expense of $174 million for 25,100 children whose families did not receive payments by March 31, 2020, the end of the fiscal year.[35] Of the 25,100 children who had not received payments by March 31, 2020, 19,200 children had received invitation letters to apply for interim one-time funding but either had not responded or their application was still being processed, while 5,900 children had yet to receive letters to apply for funding.

In summary, as of the writing of this report, the ministry has recorded unaudited autism services spending of $608 million in 2019-20, which includes an accrued expense of $174 million for 25,100 children who did not receive any payments in the 2019-20 fiscal year. Given the unique circumstances in this case, MPPs should confirm with the Auditor General of Ontario that the Province can record the full accrued expense of $174 million as spending in 2019-20.

Figure 5: Spending on autism services, 2019-20 (millions)

Source: FAO analysis of data from the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

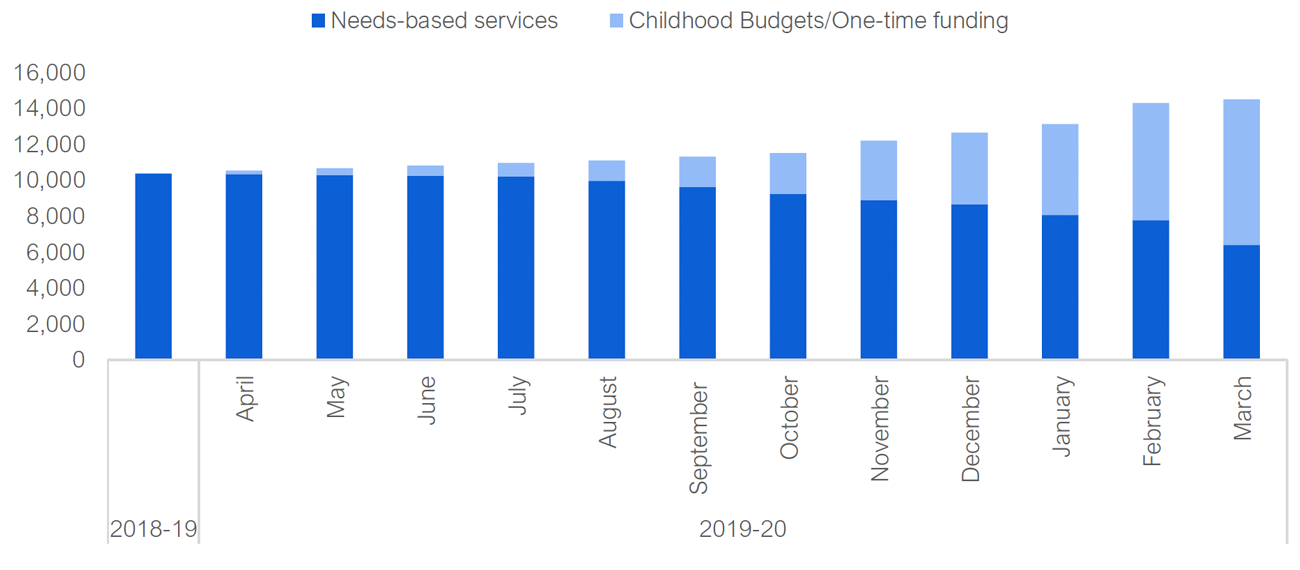

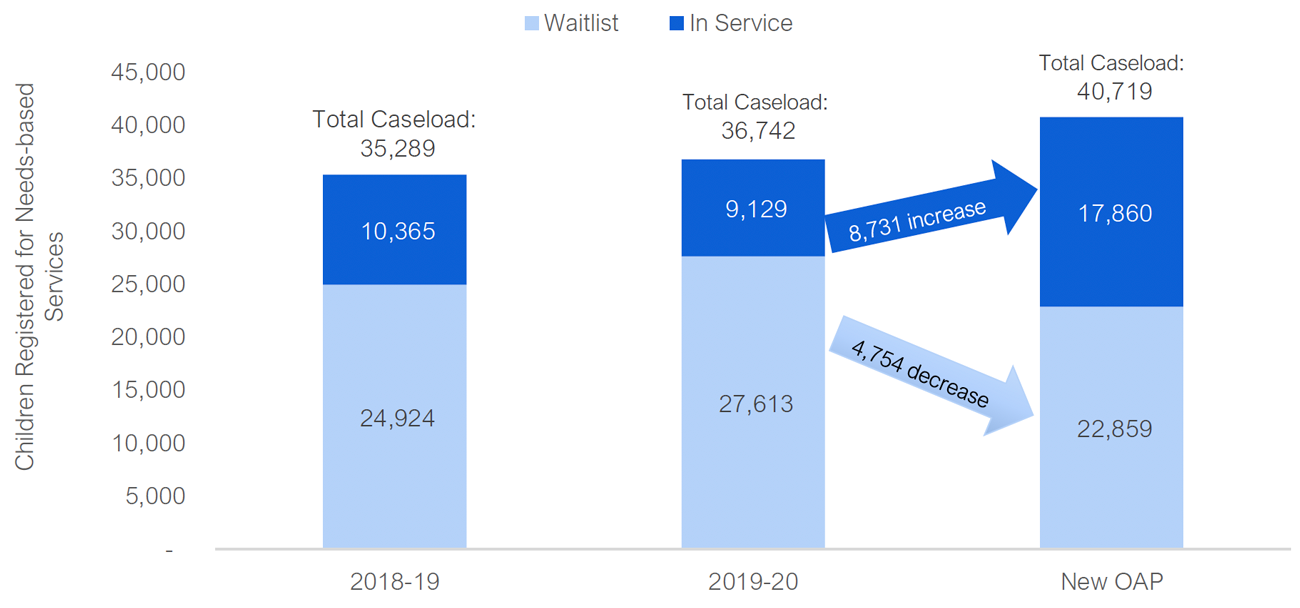

Number of Clients in 2018-19 and 2019-20

In 2018-19, 10,365 children received needs-based support under the OAP. In 2019-20, with the introduction of Childhood Budgets, the Province no longer accepted new needs-based clients. As a result, the number of clients that received needs-based funding decreased over 2019-20 as behavioural therapy plans were completed.[36] Over this period, some of the children who were on the waitlist to receive needs-based support or had completed their behavioural therapy plan began to receive Childhood Budgets or interim one-time funding.

By the end of 2019-20, approximately 14,500 children were receiving autism services, either as needs-based support or through Childhood Budgets, an increase from 10,365 clients in 2018-19. This included 6,400 children who received needs-based support[37] and 8,100 children whose families received Childhood Budgets or interim one-time funding.

Figure 6: Number of children who received autism services in 2018-19 and 2019-20

Note: In 2019-20, the average number of needs-based clients over the 12-month period was 9,129.

Source: FAO analysis of data from the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

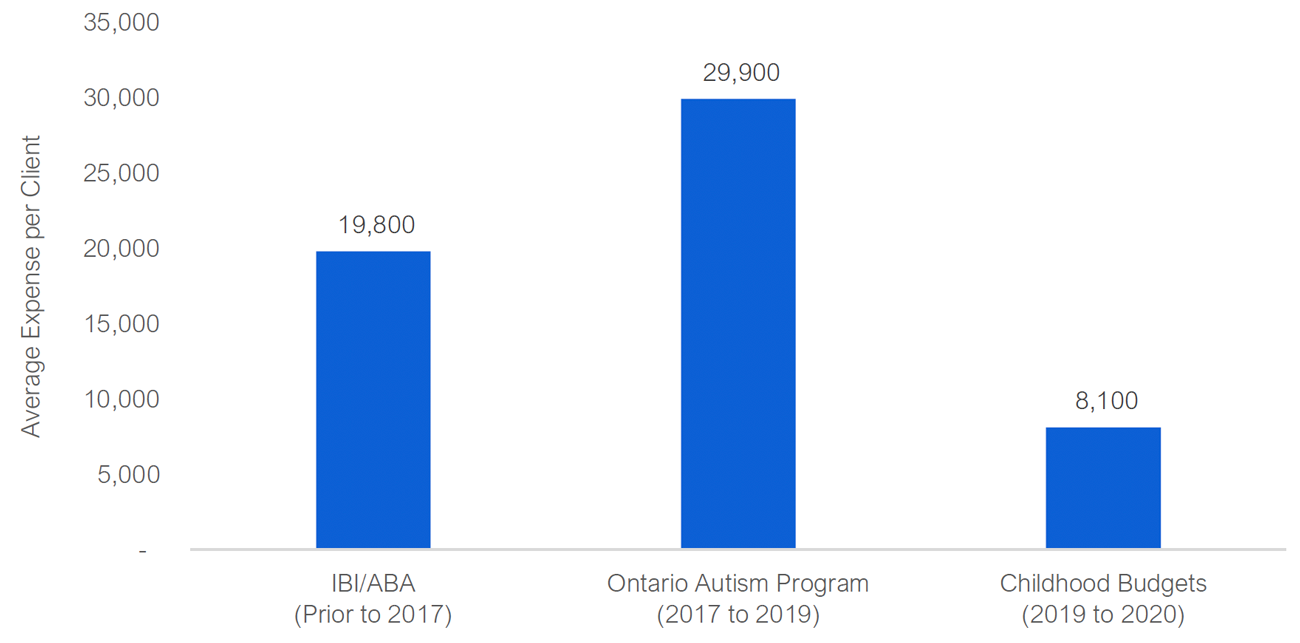

Average Spending per Client under Different Support Programs

Since 2011, the Province has offered three distinct autism programs: IBI/ABA programs (from 2011 to 2017), the OAP (from 2017 to 2019) and Childhood Budgets (2019 and 2020). Each of the three support programs had different budgets, design and objectives, which resulted in different average annual costs per client. In today’s dollars, the FAO estimates that the average cost per client for the IBI/ABA programs was $19,800, while the average cost per client under the OAP was $29,900. The increased cost per client under the OAP, compared to IBI/ABA programs, reflected the expansion of services under the OAP, including increased availability of the more expensive IBI services and an increase in the maximum hourly rate payable for behavioural services.

On the other hand, the average cost per client for Childhood Budgets was $8,100, reflecting the lower spending caps of $20,000 per child under the age of six and $5,000 per child aged six and older. This results in an average cost per client under Childhood Budgets that is significantly less than under either the IBI/ABA programs and the OAP.

Figure 7: Average annual spending per client under three different autism programs from 2011 to 2020 (2020 $)

Note: IBI/ABA represents historical intensive behavioural intervention and applied behavioural analysis programs between 2011 and 2017.

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

4 | The New OAP: Program Design Considerations

Overview

In October 2019, the Province’s Ontario Autism Program Advisory Panel provided recommendations to the government on the design of a new needs-based autism program with an annual budget of $600 million.[38] In December 2019, the Province announced that it was adopting the panel’s recommendations and would create a new Ontario Autism Program (OAP), including:

- core services such as behavioural analysis, speech pathology, occupational therapy and mental health services;

- foundational family services to build families’ capacity to support their child’s learning and development;

- early intervention services and school readiness programs to prepare children to enter school; and

- urgent response and complex needs services for children and youth with significant and immediate needs.[39]

The Province also announced the creation of an Implementation Working Group to assist with the design of the new OAP.[40] The working group is responsible for providing advice on the implementation of the new OAP, including service levels (length of service and intensity) for needs-based support.[41] Notably, the Province instructed the working group to provide input on the design of a program that would move a minimum of 8,000 children off the waitlist into needs-based services in the first full year of the new program. The new OAP is expected to be fully implemented by 2021.

Program Design Considerations

To support MPPs’ review of the new OAP, the FAO developed program design scenarios with the following variables: budget, service level, number of clients served and waitlist.

Scenario 1: Fixed Budget and 2019 OAP Service Level

Under the first scenario, the FAO assumed a fixed annual program budget of $600 million and a fixed needs-based service level similar to the level of support provided by the OAP in 2018 and 2019. Of the $600 million annual program budget, the FAO estimated that approximately $533 million would be available for needs-based services (mainly what the Province calls “core services”), with the remaining $67 million available for other program services (e.g., school supports for children on the autism spectrum, diagnostic hubs and respite care).[42]

Under these assumptions, the FAO projects that 17,860 children would be able to access needs-based support at an average cost per client of $29,900.

Estimated Waitlist under Scenario 1

The FAO estimates that in 2021, the scheduled date for the implementation of the new OAP, there will be 40,700 children registered for needs-based autism services in Ontario, an increase of approximately 4,000 compared to 2019-20.

As noted above, the FAO estimates that approximately 17,860 clients would receive needs-based services under the new OAP with a program budget of $600 million and a service level similar to the OAP in 2018 and 2019. As a result, compared to the 2019-20 average, an additional 8,700 children would receive needs-based support each year under the new OAP. On the other hand, the FAO projects that the waitlist for needs-based services would be 22,900, a reduction of 4,800 from the waitlist in 2019-20.[43]

As previously mentioned, the Province instructed the working group to provide input on the design of the new OAP so that 8,000 children would be moved off the waitlist for needs-based services in the first full year of the new program. Based on the FAO’s analysis, under scenario 1, over 8,000 additional children would receive needs-based service, but the waitlist would only drop by 4,800 due to the projected increase in caseload by 2021.

Finally, under this scenario, over half of the children and youth registered for needs-based autism services (56 per cent) would be on the waitlist. This would be an improvement from 2018-19 (71 per cent of registered children on the waitlist) and 2019-20 (75 per cent of registered children on the waitlist).

Figure 8: Estimated clients served and waitlist under the new OAP with fixed $600 million budget and 2019 OAP service level

Note: Figures refer to the average number of clients in a given year. Projected figures for the new OAP are for 2021-22, which is assumed to be the first full year of implementation.

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

Scenario 2: Fixed Budget and Lower Service Levels

In this scenario, the FAO maintained a fixed $600 million annual program budget but changed the level of needs-based service in order to measure the impact to the waitlist. As discussed in the previous section, with a $600 million budget and a needs-based service level that averaged $29,900 per child, the number of children in needs-based service would be approximately 17,860 with 22,859 children and youth on the waitlist.

With a fixed $600 million annual budget, lowering average service levels would allow the Province to increase the number of children that receive needs-based support and reduce the waitlist. Based on the FAO’s analysis, in order to completely eliminate the waitlist for needs-based services, the average cost per client would need to be reduced to $13,100. This would result in a significant reduction in the average level of needs-based support available per child. Compared to service levels under the OAP in 2018 and 2019, service levels in this scenario would be reduced by approximately 56 per cent.

Alternatively, if the new OAP were to provide service levels similar to IBI/ABA programs offered prior to 2017, at an average cost per child of $19,800 (in today’s dollars), then the waitlist would be reduced to 13,800. This would equate to a service level reduction compared to the 2018 to 2019 OAP of approximately one-third.

Finally, it should be noted that if the new OAP were to offer needs-based service levels that averaged $8,100 per child, similar to the average cost per child under Childhood Budgets, then the budget for the new OAP would be more than sufficient to provide services to all registered children and would result in significant underspending each year.

Figure 9: Change to waitlist with fixed $600 million budget and variable needs-based service levels

Source: FAO analysis.

Scenario 3: Increased Budget and 2019 OAP Service Level

In this scenario, the FAO maintained the needs-based service level from the 2018 and 2019 OAP, with average spending of $29,900 per child, and estimated the budget required to clear the waitlist.

As previously discussed, with a $600 million annual budget and needs-based service levels similar to the OAP in 2018 and 2019, the FAO estimates that the waitlist would be 22,859. At this level of needs-based service, every $100 million increase in the program’s annual budget would reduce the waitlist by approximately 3,350 children. In order to eliminate the waitlist entirely, the FAO estimates that the annual budget for the new OAP would more than double to $1.4 billion. This would result in approximately 40,700 children and youth receiving needs-based services with an average cost of $29,900 per child.

Figure 10: Annual program budget required to eliminate the waitlist for needs-based service if service is maintained at 2018 and 2019 OAP levels ($29,900 average cost per child) (millions)

Source: FAO analysis.

Other Considerations: Cost Pressures and Staff Availability

Cost Pressures

The government has set the annual budget for the new OAP at $600 million and has not indicated whether the OAP’s budget will increase over time. Going forward, the OAP will face demographic and price pressures which, if unaddressed through changes to the budget, will impact the waitlist or level of needs-based support available for children and youth on the autism spectrum.

The main cost pressures for the OAP are the number of children and youth on the autism spectrum and price inflation. Demand for needs-based autism services will directly increase with the number of children and youth on the autism spectrum in Ontario. Price inflation will have an indirect impact on the government’s cost of providing autism services. Needs-based autism services is heavily driven by the work of behavioural therapists and other support workers. Since wage growth typically follows price inflation over the medium-term, higher price inflation would be expected to increase wages. While most behavioural therapists are employed by external agencies rather than directly by the Province, higher wage expenses by these agencies would put pressure on the Province to either increase the OAP’s program budget or decrease the number of children that can receive needs-based services.

Overall, the FAO estimates that the population of children and youth in Ontario under the age of 18 will grow by an average annual rate of one per cent through 2025-26. Assuming that the autism prevalence rate remains stable at approximately 15 out of every 1,000 children and youth under the age of 18,[44] population growth will add a cumulative total of 1,600 children and youth registered for needs-based support by 2025-26. Over the next five years, price inflation is expected to average two per cent.[45]

Overall, given cost pressures from population growth and price inflation, the FAO estimates that to maintain the new OAP’s service levels and to ensure that the waitlist does not increase, the Province would need to increase the OAP’s annual budget by $96 million to $696 million by 2025-26. The $96 million budget increase represents $47 million to address population growth (to maintain the waitlist) and $49 million for price inflation (to maintain service levels).

Figure 11: Projected increase to the new Ontario Autism Program’s budget to address population growth (to maintain the waitlist) and price inflation (to maintain service levels), 2021-22 to 2025-26 ($ millions)

Source: FAO analysis.

Availability of Qualified Clinicians

In addition to cost pressures, there is a risk that the delivery of the new OAP could be constrained by the supply of needs-based therapeutic services for children and youth on the autism spectrum. As the Province expands needs-based services to more children, it will need a sufficient availability of qualified behavioural clinicians, speech language pathologists and occupational therapists to provide needs-based services.

The Ontario Autism Program Advisory Panel’s report found that concern exists in the autism community that service providers might not have the capacity to accommodate the expansion of needs-based services.[46] In addition, during the transition to Childhood Budgets in 2019, there were reports of autism service provider layoffs, which could further constrain the availability of therapists and other service providers required to implement the new OAP.[47]

The FAO questioned the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services on the supply of qualified behavioural clinicians, speech language pathologists and occupational therapists necessary to accommodate the expansion of needs-based services under the new OAP. The ministry responded that limited information was available on the autism services labour market and that the ministry was in the process of collecting information to confirm the availability, distribution and competencies of existing behavioural clinicians, speech language pathologists and occupational therapists, and the number of clinicians needed to meet current and future demand under the new OAP.

5 | Appendix

A. Development of this Report

Authority

The Financial Accountability Officer accepted a request from a member of the Legislative Assembly to undertake the analysis presented in this report under paragraph 10(1)(b) of the Financial Accountability Officer Act, 2013.

Key Questions

The following key questions were used as a guide while undertaking research for this report:

- What programs exist to support children and youth on the autism spectrum?

- How are the programs structured?

- How much has the Province spent on the programs since 2000?

- How was the Ontario Autism Program structured in 2017 and what changes were made to the program through to the end of 2019-20?

- How much did the program cost?

- How did the waitlist change?

- What are the recent developments (i.e., childhood budgets, interim one-time funding)?

- What is the Province’s new Autism program?

- Autism program analysis:

- What would the program cost if all children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder receive needs-based supports as provided under the previous Ontario Autism Program?

- What would the size of the waitlist be if the program is limited to an annual $600 million budget and participants receive needs-based support as provided under the previous Ontario Autism Program?

- What would be the level of needs-based support if the waitlist is eliminated and the budget is held to $600 million?

- What are the implementation risks?

- Are there enough service providers to meet demand?

Methodology

This report has been prepared with the benefit of information provided by, and meetings with staff from, the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services and a review of relevant literature and other publicly available information. Specific sources are referenced throughout.

All dollar amounts are in Canadian, current dollars (i.e., not adjusted for inflation) unless otherwise noted.

About this document

Established by the Financial Accountability Officer Act, 2013, the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) provides independent analysis on the state of the Province’s finances, trends in the provincial economy and related matters important to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario.

The FAO produces independent analysis on the initiative of the Financial Accountability Officer. Upon request from a member or committee of the Assembly, the Officer may also direct the FAO to undertake research to estimate the financial costs or financial benefits to the Province of any bill or proposal under the jurisdiction of the legislature.

This report was prepared on the initiative of the Financial Accountability Officer in response to a request from a member of the Assembly. In keeping with the FAO’s mandate to provide the Legislative Assembly of Ontario with independent economic and financial analysis, this report makes no policy recommendations.

This report was prepared by Michelle Gordon and Greg Hunter, under the direction of Luan Ngo and Jeffrey Novak.

External reviewers provided comments on early drafts of this report. The assistance of external reviewers implies no responsibility for this final report, which rests solely with the FAO.

Graphic Descriptions

Source: FAO analysis of data from the Ministry of Children, Community, and Social Services

Source: FAO analysis of data from the Ministry of Children, Community, and Social Services.

Source: FAO analysis of data from the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

Source: FAO analysis of information provided by the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

Source: FAO analysis.

Footnotes

[1] Childhood Budgets can be used to purchase a range of services, including behavioural therapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, physiotherapy, technology, family supports and respite care.

[2] Accrued expenses are expenses that are incurred and recognized in one accounting period but will not be paid until a later date. Under the Province’s accrual method of accounting, expenses are recognized when they are incurred, not necessarily when they are paid.

[3] Of the 25,100 children who had not received payments by March 31, 2020, 19,200 children had received invitation letters to apply for interim one-time funding but either had not responded or their application was still being processed, while 5,900 children had yet to receive letters to apply for funding.

[4] The waitlist for needs-based services in 2019-20 includes 8,100 children who received Childhood Budgets or interim one-time funding.

[5] The Ontario Autism Program Advisory Panel’s report found that concern exists in the autism community that service providers might not have the capacity to accommodate the expansion of needs-based services. In addition, during the transition to Childhood Budgets in 2019, there were reports of autism service provider layoffs, which could further constrain the availability of therapists and other service providers required to implement the new OAP.

[6] Autism Ontario, “Autism Spectrum Disorder,” 2020.

[7] National Institute on Deafness and Other Communications Disorders, “Autism Spectrum Disorder: Communication Problems in Children.” https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/autism-spectrum-disorder-communication-problems-children.

[8] Autism Canada, “About Autism: Characteristics.” https://autismcanada.org/about-autism/characteristics/.

[9] Government of Canada, "Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children and Youth in Canada 2018." https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/diseases-conditions/autism-spectrum-disorder-children-youth-canada-2018/autism-spectrum-disorder-children-youth-canada-2018.pdf.

[10] Auditor General of Ontario, “2013 Annual Report: Autism Services and Supports for Children,” 2013. https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en13/2013ar_en_web.pdf.

[11] Based on 25 hours per week and 50 weeks per year, costing $75 per hour (https://www.kidsability.ca/uploads/Firefly/Behavioural%20Services/Firefly_IBIServices_Fall2016.pdf) or $1,900 per week (https://www.cheo.on.ca/en/clinics-services-programs/resources/Documents/Autism/2019AutismGuideENG.pdf).

[12] Intensive behavioural intervention therapy services typically costs between $40,000 and $80,000 per year. https://www.ontaba.org/pdf/ABA%20Primer.pdf.

[13] Daniel Kitts, “Understanding the Difference Between ABA and IBI Autism Treatments,” TVO.org, April 2016. https://www.tvo.org/article/understanding-the-difference-between-aba-and-ibi-autism-treatments.

[14] Outside of MCCSS, the Ministry of Education also provides funding for students on the autism spectrum through the Special Education Grant, which funds special equipment, additional staffing, care for individuals in special facilities and ABA training. The Ministry of Education also provides support for students on the autism spectrum as they transition into the school environment and for training educators.

[15] By 2018-19, the average wait time to access needs-based services was 18.2 months, up from an average wait time of 14.9 months in 2014-15.

[16] The waitlist for needs-based services in 2019-20 includes 8,100 children who received Childhood Budgets or interim one-time funding.

[17] Childhood Budgets can be used to purchase a range of services, including behavioural therapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, physiotherapy, technology, family supports and respite care.

[18] Estimated based on information in Auditor General of Ontario, “2013 Annual Report: Autism Services and Supports for Children,” 2013. Adjusted for inflation, average spending per client was $19,800 in 2020 dollars.

[19] Government of Ontario, “Ontario Creating Expert Committee on Autism,” December 2012. https://news.ontario.ca/mcys/en/2012/12/ontario-creating-expert-committee-on-autism.html.

[20] Autism Spectrum Disorder Clinical Expert Committee, “Autism Spectrum Disorder in Ontario, 2013: An update on Clinical Practice Guidelines and Benchmarks in Ontario,” January 2014. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B2CvyPKQNuQBYVVlTzhEa1FoQm8/view.

[21] Government of Ontario,“Strengthening the Ontario Autism Program,” June 2016. https://news.ontario.ca/mcys/en/2016/06/strengthening-the-ontario-autism-program.html.

[22] Integrated autism services refers to a program with standardized eligibility criteria, one enrolment process and one waitlist for all services, including both ABA and IBI therapy. Previously, children could be on both an ABA waitlist and an IBI waitlist or receive one type of service while waiting for another.

[23] Government of Ontario, “Strengthening the Ontario Autism Program,” June 2016. https://news.ontario.ca/mcys/en/2016/06/strengthening-the-ontario-autism-program.html.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Government of Ontario, “Ontario Takes Decisive Action to Help More Families with Autism,” February 2019. https://news.ontario.ca/mcys/en/2019/02/ontario-takes-decisive-action-to-help-more-families-with-autism.html.

[27] On July 29, 2019, the Province announced that a second six-month extension would be be allowed. Government of Ontario, “Ontario is Working Towards a Needs-Based and Sustainable Autism Program,” July 29, 2019. https://news.ontario.ca/mcys/en/2019/07/ontario-is-working-towards-a-needs-based-and-sustainable-autism-program.html.

[28] Government of Ontario, “Ontario Enhancing Support for Children with Autism,” March 2019. https://news.ontario.ca/mcys/en/2019/03/ontario-enhancing-support-for-children-with-autism.html. Government of Ontario, “Ontario is Working Towards a Needs-Based and Sustainable Autism Program,” July 2019. https://news.ontario.ca/mcys/en/2019/07/ontario-is-working-towards-a-needs-based-and-sustainable-autism-program.html.

[29] Government of Ontario, “Province Consulting with Parents on Enhancements to the Ontario Autism Program,” April 2019. https://news.ontario.ca/mcys/en/2019/04/province-consulting-with-parents-on-enhancements-to-the-ontario-autism-program.html.

[30] Government of Ontario, “Ontario to Implement Needs-Based Autism Program In-Line with Advisory Panel’s Advice,” December 17, 2019. https://news.ontario.ca/mcys/en/2019/12/ontario-to-implement-needs-based-autism-program-in-line-with-advisory-panels-advice.html.

[31] Includes interim one-time funding.

[32] The $321 million budget included $62 million that was placed on administrative “holdback.” Although in the 2018-19 Expenditure Estimates the government requested from the legislature $321 million in spending authority for autism programs, Treasury Board, a Cabinet committee, placed $62 million of the $321 million budget on administrative holdback. This prevented the ministry from spending the $62 million in funds until further approval was received from Treasury Board, which was granted later in the 2018-19 fiscal year. Treasury Board will often place all or a portion of a program’s budget on holdback for various administrative and oversight reasons, including to ensure that ministries develop adequate plans for new or expanded programs or meet contractual obligations, before receiving authority to spend funds.

[33] From FAO correspondence with the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

[34] Based on the FAO’s review of the Province’s integrated financial information system (IFIS), as of May 14, 2020.

[35] Accrued expenses are expenses that are incurred and recognized in one accounting period but will not be paid until a later date. Under the Province’s accrual method of accounting, expenses are recognized when they are incurred, not necessarily when they are paid.

[36] Families of children receiving needs-based support also had the option to extend their behavioural therapy plan for 12 months (two six-month extensions).

[37] In 2019-20, the average number of needs-based clients over the 12-month period was 9,129.

[38] Available at: http://www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/documents/specialneeds/autism/AutismAdvisoryPanelReport_2019.pdf.

[39] Government of Ontario, “Ontario To Implement Needs-Based Autism Program In-Line with Advisory Panel’s Advice,” December 2019. https://news.ontario.ca/mcys/en/2019/12/ontario-to-implement-needs-based-autism-program-in-line-with-advisory-panels-advice.html

[40] Ibid.

[42] The FAO’s estimate of $533 million available for needs-based services and $67 million for other autism program services is based on historical spending trends (see Figure 4 for more details). Actual funding allocation will depend on the final design of the new OAP.

[43] Under the new OAP, the increase in the number of clients served would be partially offset by the increase in the total caseload by 2021, resulting in a net decrease to the waitlist of 4,800.

[44] If autism becomes more widespread across the population, the number of people seeking support would increase over and above the growth in the population of children and youth under the age of 18.

[45] See FAO, “Economic and Budget Outlook,” Spring 2020.

[46] See, “The Ontario Autism Program Advisory Panel Report,” October 2019, p. 29. Available at: http://www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/documents/specialneeds/autism/AutismAdvisoryPanelReport_2019.pdf.

[47] For example, see Windsor Star, “McGivney Children’s Centre Announces Layoffs to Autism Workers,” April 2, 2019. https://windsorstar.com/news/local-news/mcgivney-childrens-centre-announces-layoffs-to-autism-workers/.