1 | Key Points

- Broad-based shutdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic are projected to result in a 5.9 per cent drop in Ontario real GDP in 2020, the largest annual decline in economic output on record. Assuming vaccines are distributed to the general population over the course of 2021 and government lockdown restrictions are progressively eased, Ontario’s economy is expected to rebound strongly with growth of 3.9 per cent in 2021 and 4.5 per cent in 2022.

- The pandemic caused a sharp decline in revenue and a significant increase in program spending, leading to a record budget deficit of $35.5 billion in 2020-21. As the province recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic and the economy rebounds, the budget deficit is expected to remain elevated at $30.7 billion in 2021-22, improving to $16 billion over the extended projection, in the absence of policy changes. When the budget is in deficit, the Province must develop a fiscal recovery plan that specifies how and when the budget will be balanced.

- Much of the significant increase in program spending projected in 2020-21 is due to temporary COVID-19 expenditures. Excluding COVID-19 funds, planned program spending growth in key sectors, including health and education, will not keep pace with the underlying demand for public services over the next two years.

- In addition to temporary COVID-19 spending, the 2020 Budget allocated $3.0 billion to its standard contingency funds in 2020-21, which grow over the 2021-22 to 2022-23 period and are much larger than usual. The government has yet to clearly indicate the specific purpose of the sharp increase in these funds after the pandemic. Any unused contingency funds would be applied to reduce projected deficits.

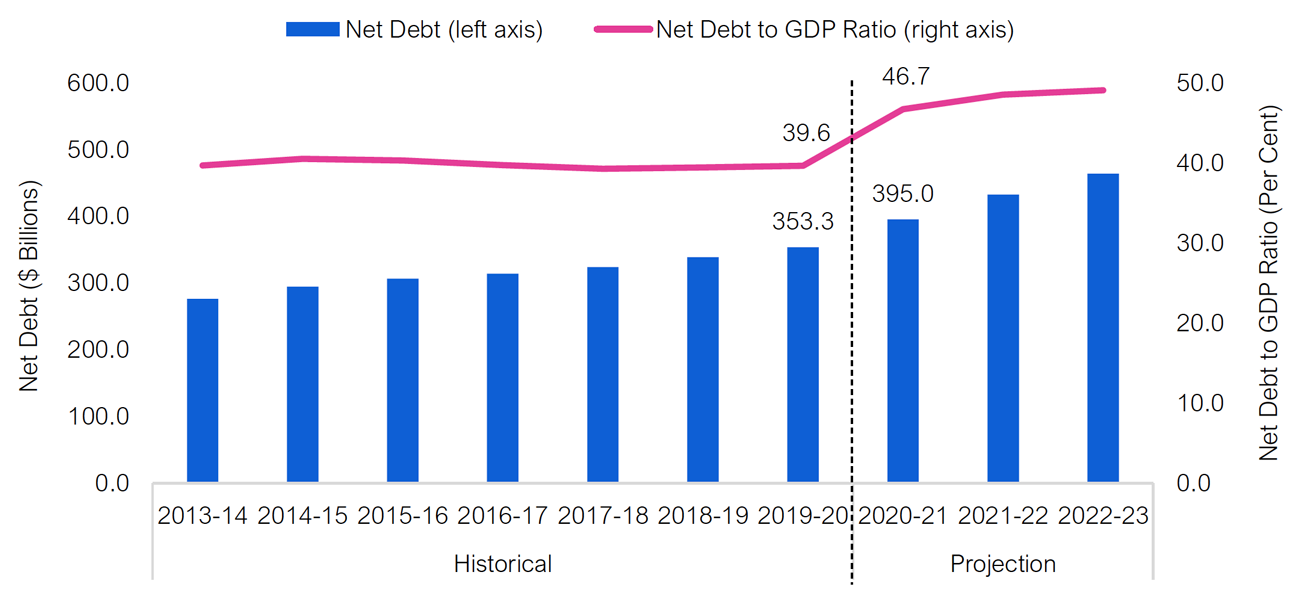

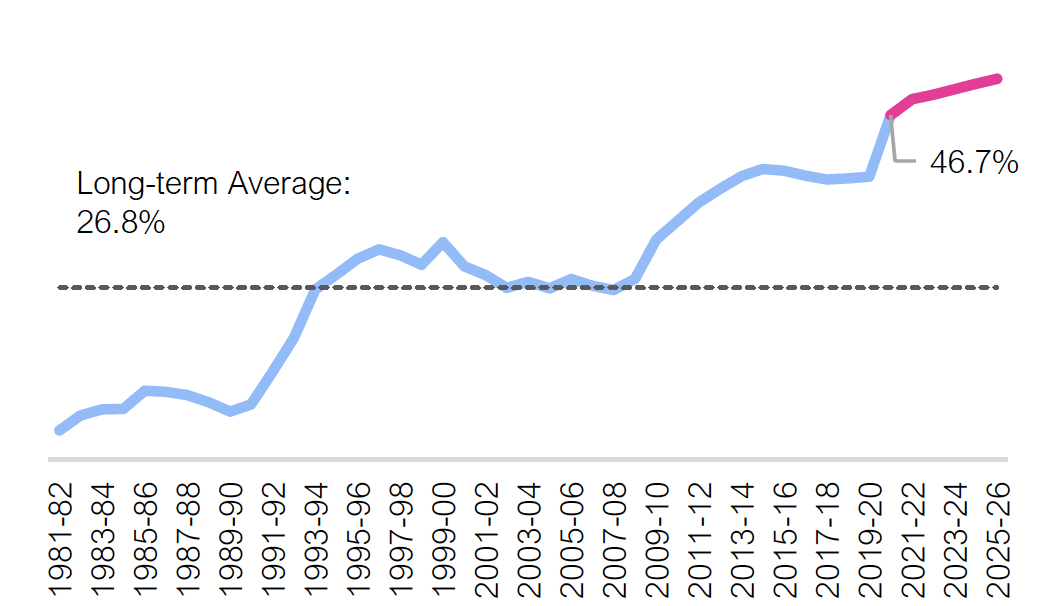

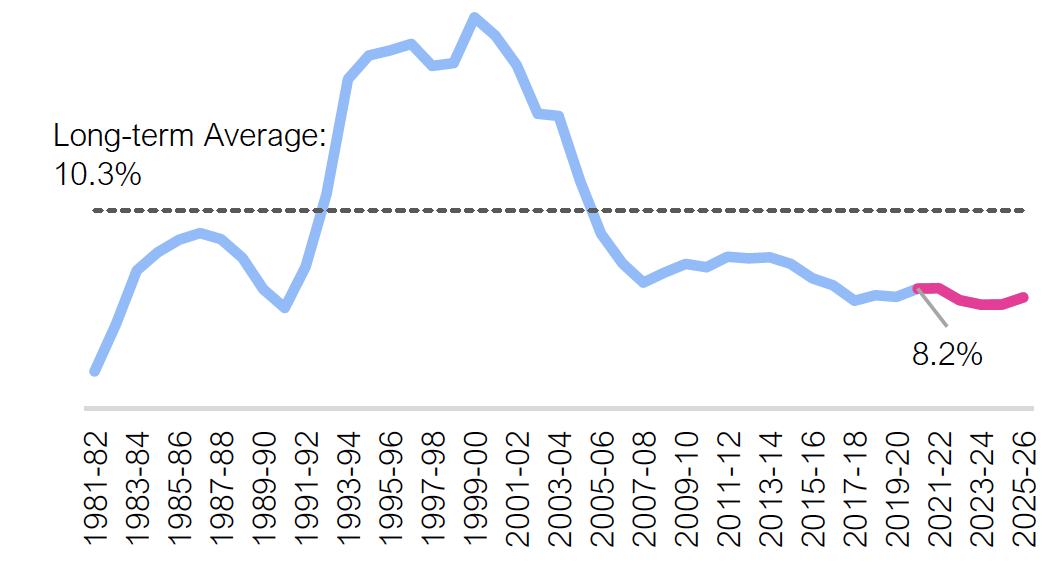

- The province’s debt burden increased significantly in 2020-21, and net debt as a share of GDP is projected to reach 50 per cent by 2025-26 in the absence of policy changes. This could make the province more vulnerable to unexpected interest rate increases in the future. However, the cost of financing the large increase in debt will be manageable over the outlook if interest rates remain near historic lows, as currently expected.

2 | Summary

Ontario economy expected to rebound after record decline in 2020

Broad-based shutdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring resulted in a historic negative shock to Ontario’s economy over the first half of 2020. Initial government measures to contain the virus and provide financial support for households and businesses led to a strong rebound in the economy through the summer. However, a second and larger wave of COVID-19 infections in the fall prompted renewed restrictions across the province, significantly slowing the pace of Ontario’s economic recovery late last year and early in 2021.

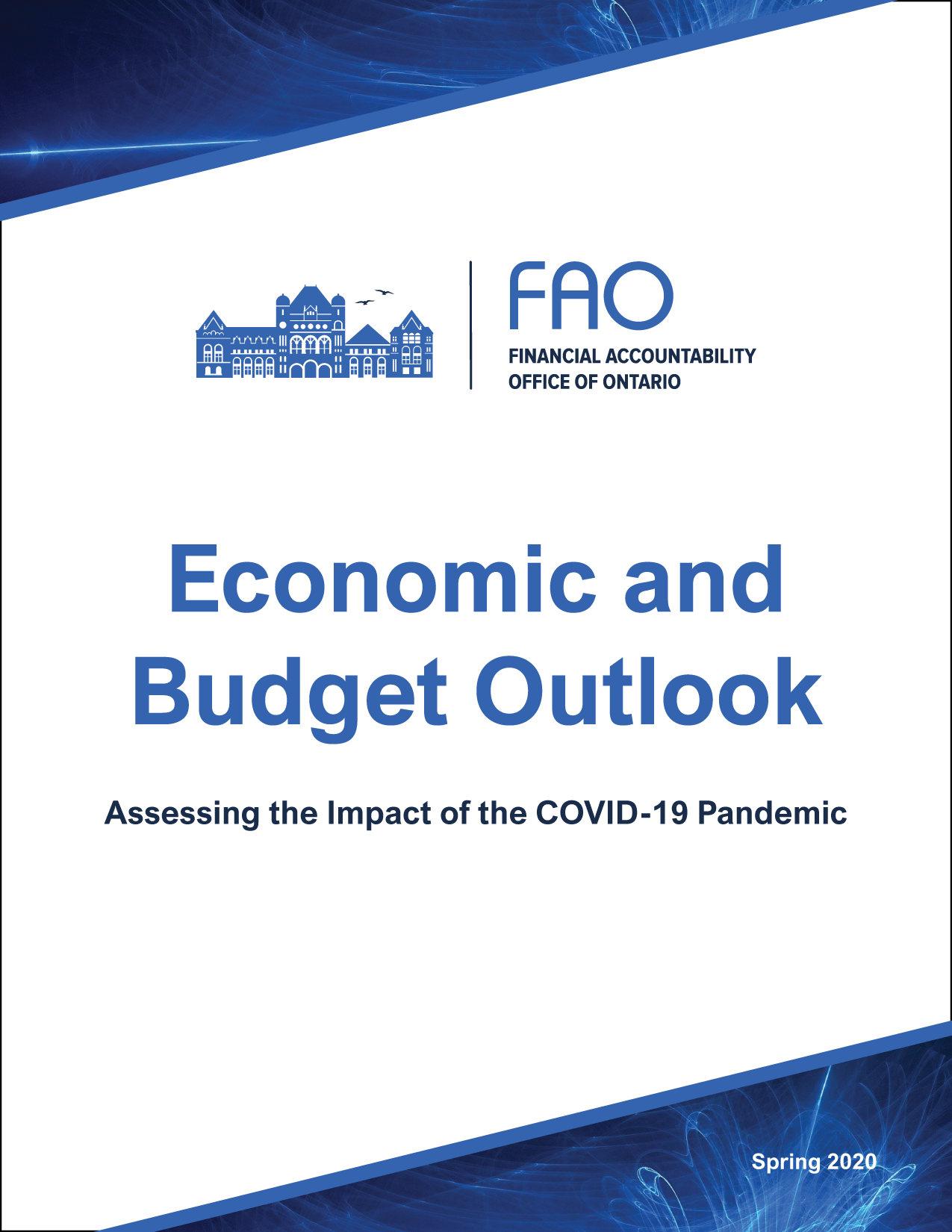

Figure 2‑1: Ontario economy to rebound in 2021

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

The FAO projects Ontario real GDP will drop by 5.9 per cent in 2020, the largest annual decline in economic output on record.[1] Assuming vaccines are distributed to the general population over the course of 2021 and that social distancing and select restrictions remain in place until early 2022, Ontario real GDP is expected to rise by 3.9 per cent in 2021 and 4.5 per cent in 2022.[2] However, economic growth would be slower than projected if public vaccinations are significantly delayed, or if rising COVID-19 hospitalizations necessitate more prolonged or extensive economic shutdowns this winter.

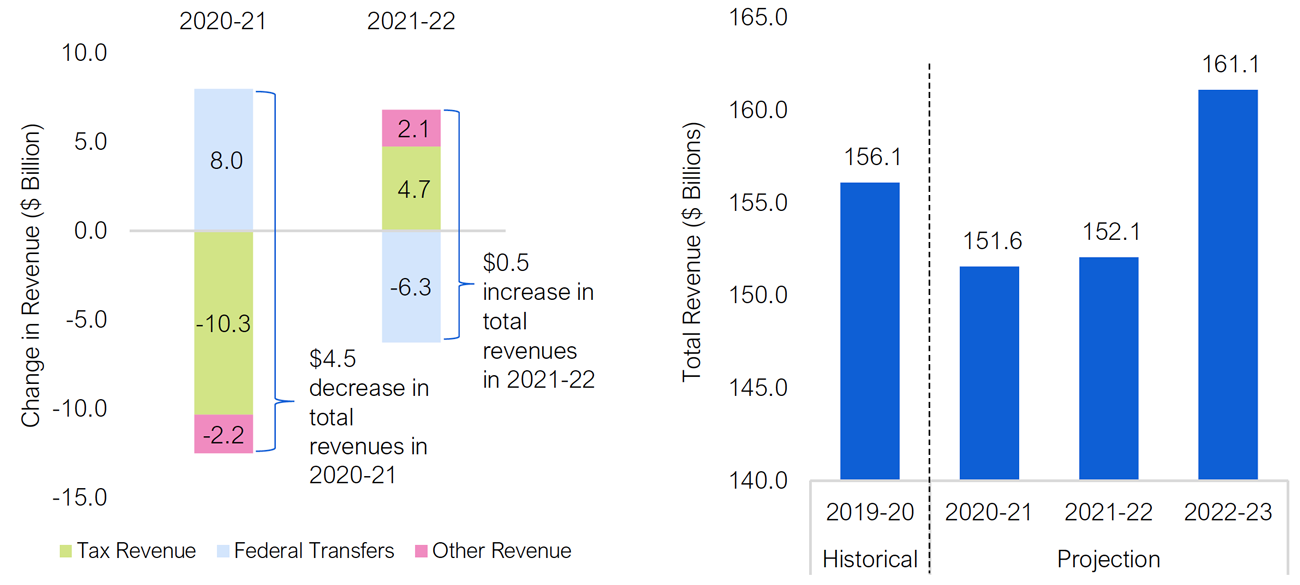

Revenues drop as a result of pandemic

As the pandemic continues, total revenues are expected to decline sharply in 2020-21 by $4.5 billion, a decline of 2.9 per cent. The drop in overall revenues results from a substantial $10.3 billion decline in tax revenues which is partially offset by a significant $8.0 billion increase in transfers from the federal government, largely consisting of one-time COVID-related support.

Despite the economic rebound, 2021-22 revenues are expected to remain largely unchanged as the increase in tax revenues is offset by a reduction in federal transfers. As the economy is more fully reopened, revenue growth picks up in 2022-23.

Program spending growth in key sectors will not keep pace with demand for public services

In response to the pandemic, Ontario’s program spending in 2020-21 is projected to grow by 14.7 per cent, the largest increase since 2009-10. Most of this increase is driven by temporary COVID-19 spending. Excluding temporary COVID-19 measures, base program spending growth is expected to slow over the projection, with spending growth in key sectors including health and education to lag the demand for public services.

The 2020 Budget allocated $3.0 billion to its standard contingency funds in 2020-21, significantly above the usual size and in addition to the temporary COVID-19 funds. Over the next two years, the allocation to the standard contingency funds will increase even further. While contingency funds are maintained to manage expense risks, the government has not clearly indicated the purpose of the sharp increase in these funds after the pandemic. Importantly, if these contingency funds are not used for new programs or future unforeseen events, they may be used to reduce deficits.

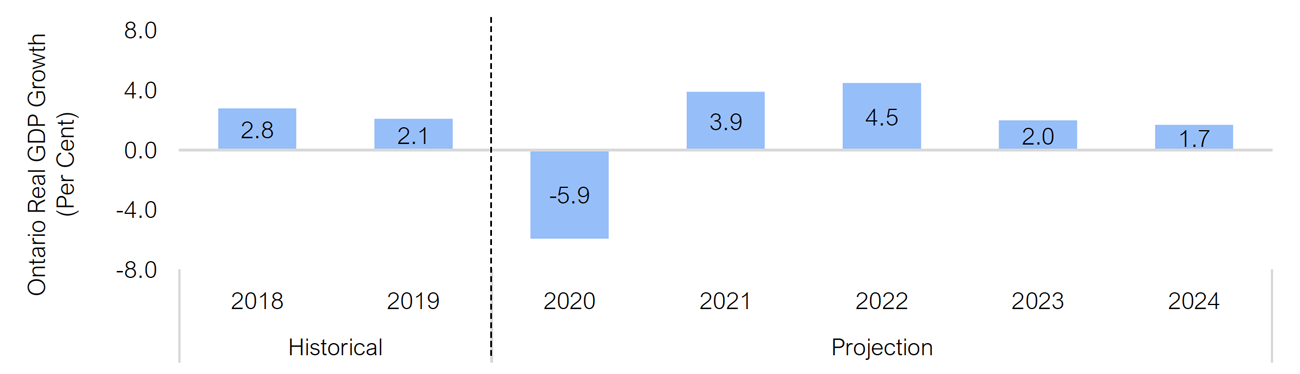

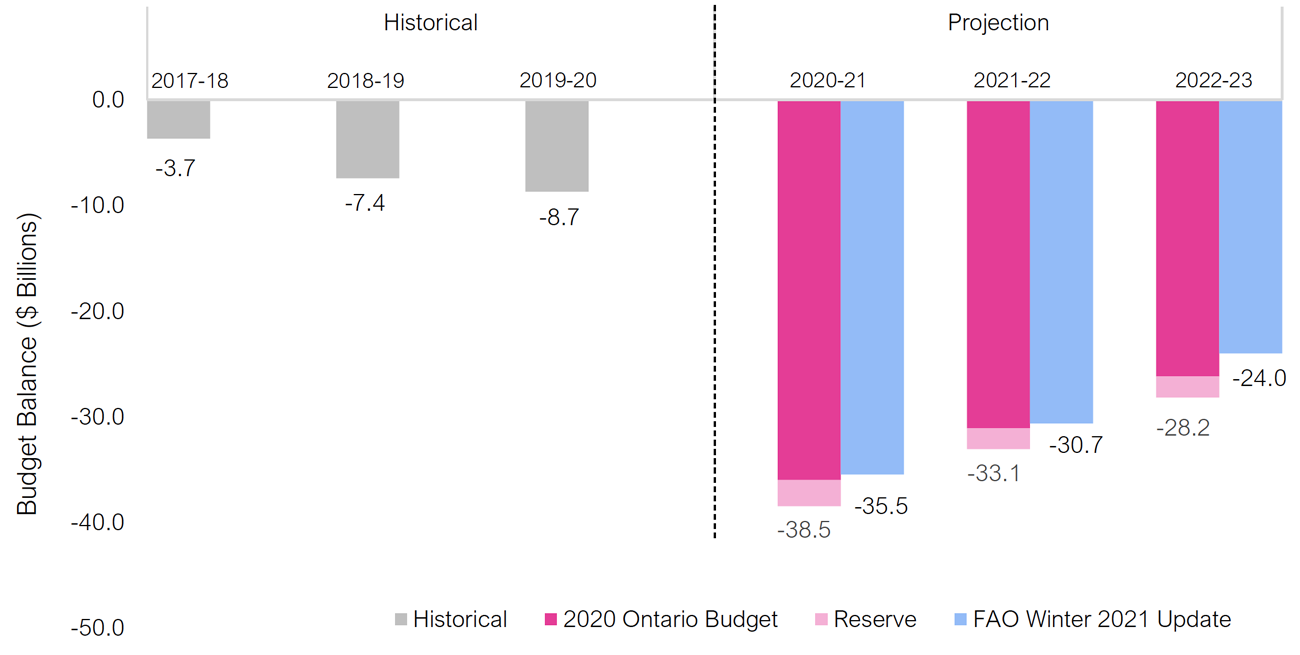

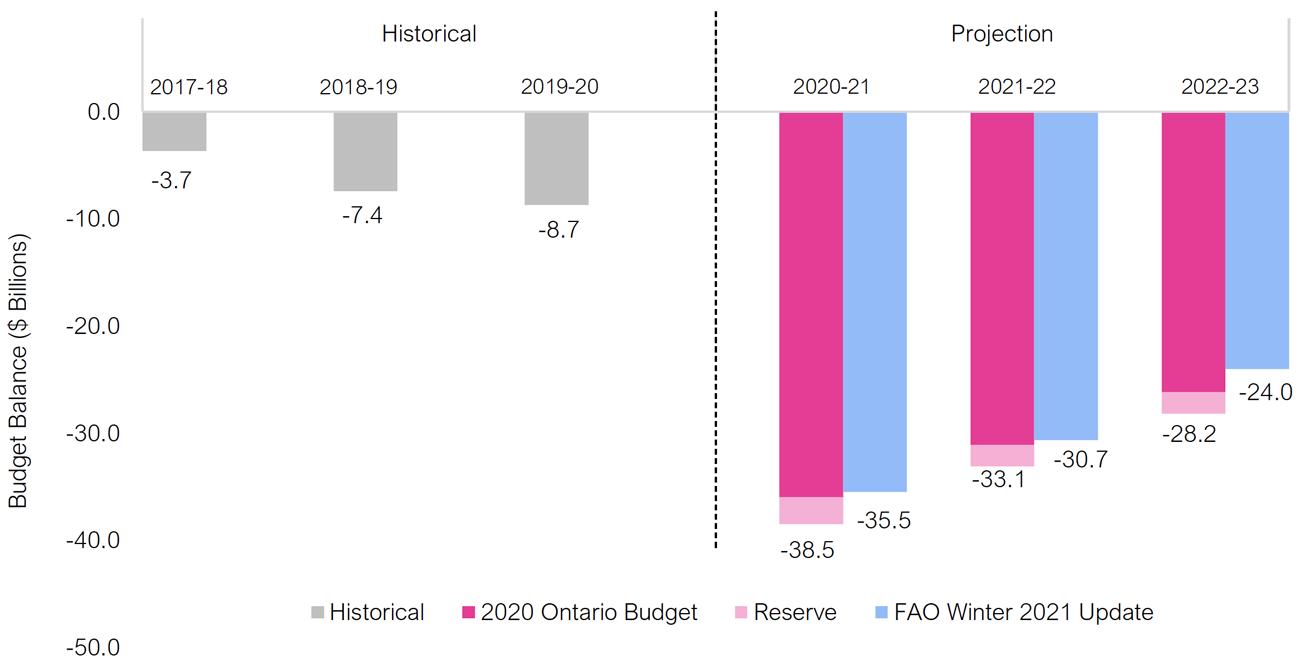

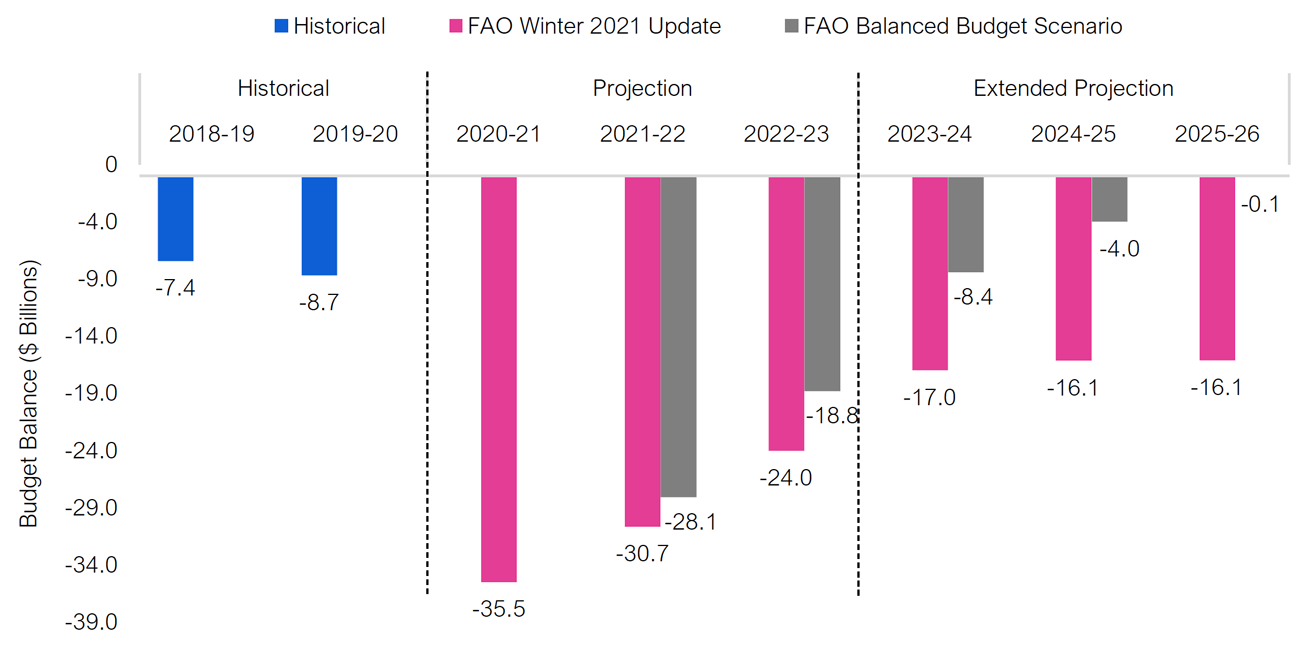

Ongoing deficits projected for Ontario

The FAO projects Ontario’s budget deficit will increase from $8.7 billion in 2019-20 to a record $35.5 billion in 2020-21. As the province recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic and the economy rebounds, the budget deficit is expected to remain elevated at $30.7 billion in 2021-22 and improve modestly to $24 billion in 2022-23. Beyond 2022-23 the FAO projects that the deficit will stabilize at around $16 billion in the absence of further policy changes.

Figure 2‑2: Ontario projected to have large ongoing budget deficits

Note: The FAO Winter 2021 Budget Balance is presented without the reserve.

Source: 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

In Ontario, the Fiscal Sustainability, Transparency and Accountability Act, 2019 (FSTAA) requires that when the budget is in deficit, the Province must develop a fiscal recovery plan that specifies how and when the budget will be balanced. The government committed to present a multi-year fiscal recovery plan in the 2021 Ontario budget, to be delivered by March 31, 2021.

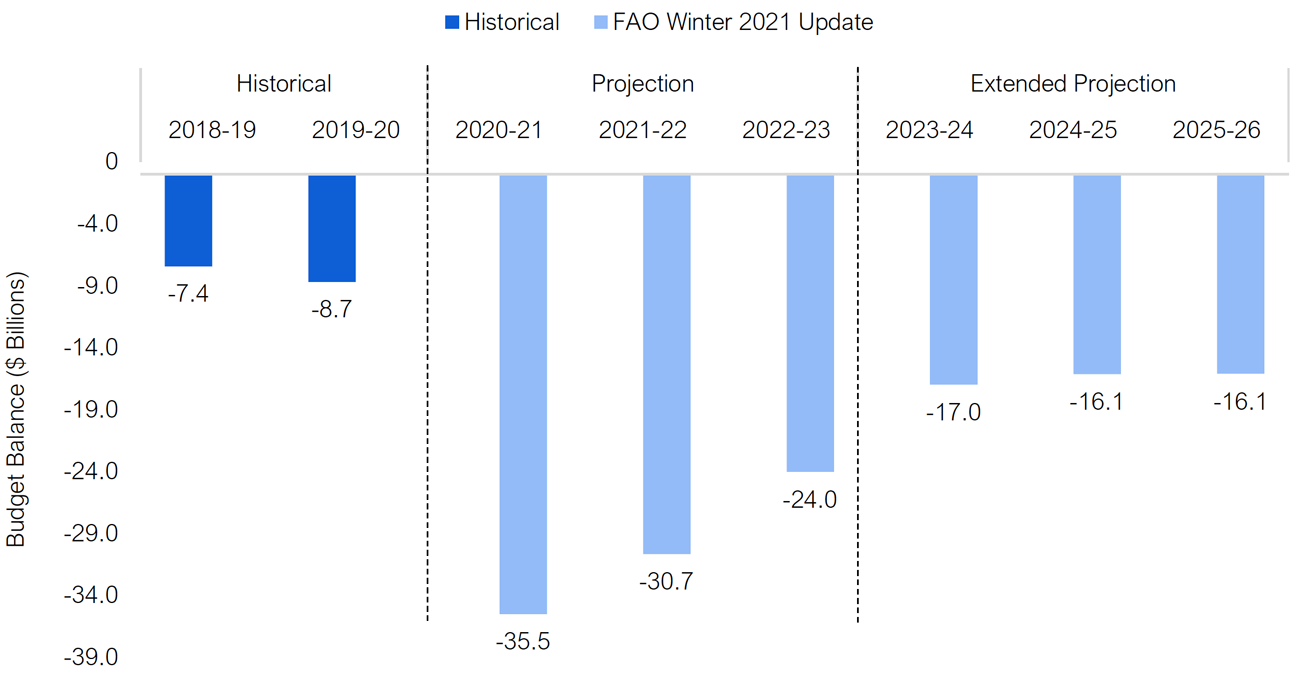

Low interest rates offset the cost of rising debt over the outlook

Net debt is expected to rise sharply by $41.7 billion, to $395 billion in 2020-21, pushing the net debt-to-GDP ratio up to 46.7 per cent. Large and continued deficits add to debt and raise the net debt-to-GDP ratio over the outlook, which reaches almost 50 per cent by 2022-23 – 10 percentage points higher than the pre-pandemic ratio.

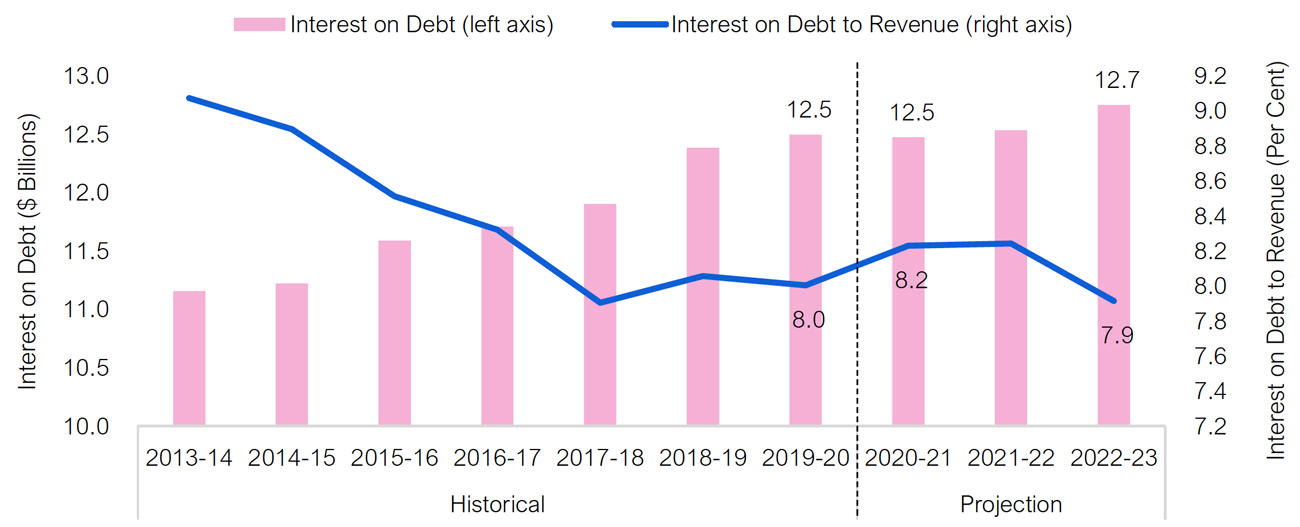

However, the cost of financing the large increase in provincial debt is expected to be manageable over the medium term. As a share of revenue, interest on debt is expected to rise to 8.2 per cent in 2020-21, as revenues decline due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As the economy and provincial revenues rebound, interest payments as a share of revenues are expected to decline to 7.9 per cent by 2022-23, similar to its pre-pandemic share.

Figure 2‑3: Interest on debt payments to remain largely unchanged over the medium term

Source: Ontario Public Accounts and FAO.

This outcome is largely due to the expectation that interest rates will remain near historic lows over the outlook. However, the significant increase in debt leaves the province more vulnerable to unexpected interest rate increases in the future.

3 | Economic Outlook

Overview

Broad-based shutdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring resulted in a historic negative shock to the Ontario economy over the first half of 2020. Initial government measures to contain the virus and provide financial support for households and businesses led to a strong rebound in the economy through the summer. However, a second and larger wave of COVID-19 infections in the fall has prompted renewed restrictions across the province, significantly slowing the pace of Ontario’s economic recovery late last year and early in 2021. Given high COVID-19 caseloads and hospitalizations, the FAO expects stringent restrictions will remain in place through much of the winter, followed by a slow reopening during the rest of the year as vaccinations become increasingly available. As a result, the projected rebound in economic activity in 2021 will be more muted than previously expected.

The FAO projects Ontario real GDP will drop by 5.9 per cent in 2020, the largest annual decline in economic output on record.[3] Assuming vaccines are distributed to the general population over the course of 2021 and that social distancing and select restrictions remain in place until early 2022, Ontario real GDP is expected to rise by 3.9 per cent in 2021.[4] As the majority of the Canadian population becomes immunized and the economy is more fully reopened, economic growth is expected to strengthen further in 2022, with real GDP rising by 4.5 per cent. However, economic growth would be slower than projected if public vaccination is significantly delayed, or if rising COVID-19 hospitalizations necessitate more prolonged or extensive economic shutdowns this winter.

Ontario nominal GDP, which provides a broad measure of the tax base, is projected to decline by 5.2 per cent in 2020, reflecting a decline in labour income and sharply lower corporate profits. Nominal GDP is expected to rebound strongly in 2021 and 2022, growing by 5.4 and 6.0 per cent, respectively.

Figure 3‑1: Ontario economy expected to rebound strongly in 2021 and 2022

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

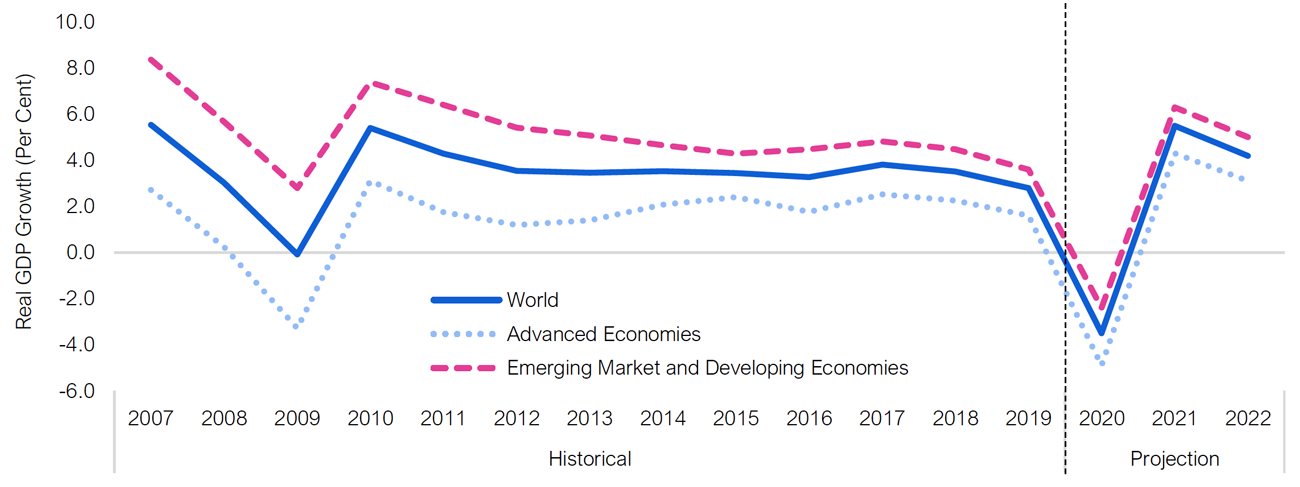

Global economy projected to grow strongly in 2021

Following a strong initial economic recovery in mid-2020, many countries have experienced renewed COVID-19 outbreaks and reinstated containment measures, raising concerns of a second economic downturn and a prolonged recovery. However, strong fiscal and monetary policy support and the rapid success of international COVID-19 vaccine research will provide support for a global recovery in 2021. Based on these developments, the IMF now projects the global economy will decline by 3.5 per cent in 2020, surpassing the drop in economic activity during the 2008-2009 global financial crisis. Assuming the pandemic is steadily contained over the next two years, the IMF projects global real GDP will rise by 5.5 per cent in 2021. The pace of economic recovery is expected to be uneven across countries and will depend on the success of containment measures, the extent of policy support for the economy, and access to vaccination.

Figure 3‑2: Global real GDP projected to rise by 5.5 per cent in 2021

Source: IMF.

In the United States, real GDP is projected to decline by 3.5 per cent in 2020, reflecting widespread virus outbreaks and uneven impacts across sectors. While high caseloads are likely to persist in the near term, access to vaccines and additional fiscal stimulus in early 2021 are expected to relieve some pressure on the health care system and boost household income and spending. The Federal Reserve has also committed to accommodative monetary policy until its long-run goals for employment and inflation are met. Overall, US real GDP is projected to rebound by 4.0 per cent in 2021.

In Canada, where the pace of economic recovery slowed in the fall because of a second outbreak of infections, real GDP is expected to have declined by 5.7 per cent in 2020. The economic impact of the pandemic has varied across sectors. Retail sales and housing market activity initially bounced back strongly, while business capital investment and international trade have lagged due to heightened uncertainty and weak foreign demand. Sectors most affected by shutdown measures, such as accommodation and food services, culture and recreation, and transportation, continue to struggle while other sectors such as finance, insurance, real estate and some manufacturing industries have fully recovered the loss of output during the spring. Based on the assumption of expanded vaccine availability, Canada-wide real GDP is projected to rebound in 2021 and 2022 by 3.7 and 4.5 per cent, respectively.

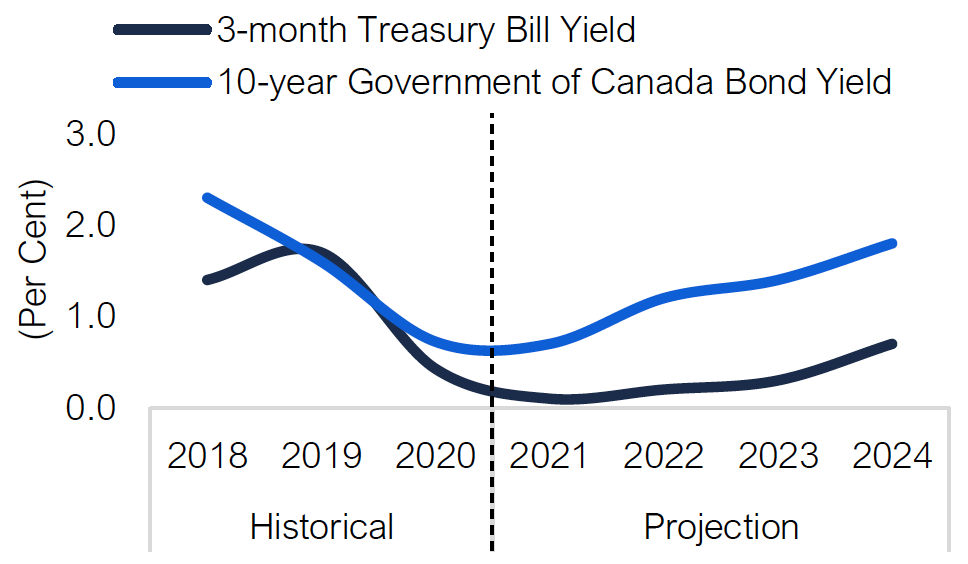

Interest rates to remain low until 2023

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

The Bank of Canada has maintained its policy interest rate at 0.25 per cent since March 2020, when the rate was lowered by 1.5 percentage points in response to the economic downturn. In the January 2021 Monetary Policy Report, the Bank affirmed its intention to continue monetary policy support and hold the rate at 0.25 per cent until the Bank’s annual inflation target of 2 per cent is achieved. According to the Bank’s projections, a slow recovery and the impact of the pandemic are expected to dampen inflation until 2023, signalling that short-term interest rates are likely to remain low over the next two years.

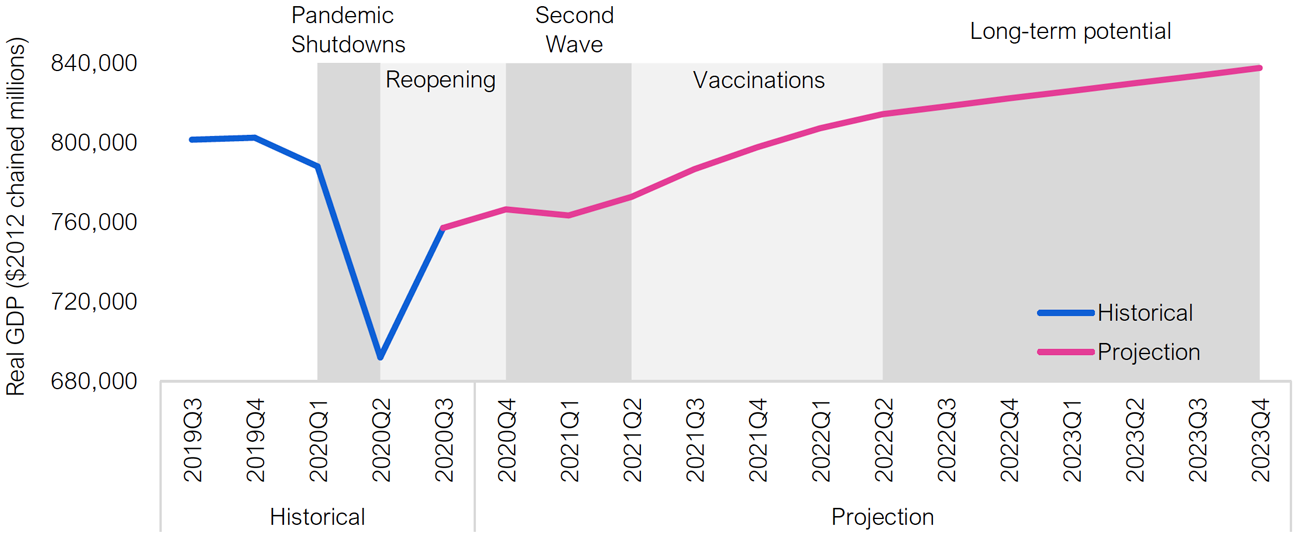

Ontario economy expected to rebound in 2021 and 2022

Following a historic negative shock to Ontario’s economy in the second quarter of 2020 caused by the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns, government actions to contain the virus combined with measures to provide financial support for households and businesses resulted in a strong rebound in the third quarter. However, renewed restrictions in response to larger waves of infections and hospitalizations in the fall and winter are expected to dampen economic activity through early 2021, leading to a weaker rebound than anticipated in the FAO’s Fall 2020 projection.

The FAO’s economic outlook assumes that an effective vaccination program is rolled out through 2021, setting the stage for a strong economic recovery by the second half of the year. Under this assumption, the FAO projects Ontario real GDP will rise by 3.9 per cent in 2021. Strong consumer spending and housing market activity are expected to lead the recovery, supported by pent-up demand, elevated household savings partly from government income support programs, and record-low mortgage rates. As much of the population becomes immunized and the economy is more fully reopened, economic growth is expected to be even stronger in 2022, with real GDP rising by 4.5 per cent. Over the 2023 to 2024 period, Ontario’s economy is expected to return to more normal conditions, with average real GDP growth of 1.9 per cent.

Figure 3‑4: Stages of Ontario real GDP growth

Source: Ontario Economic Accounts and FAO.

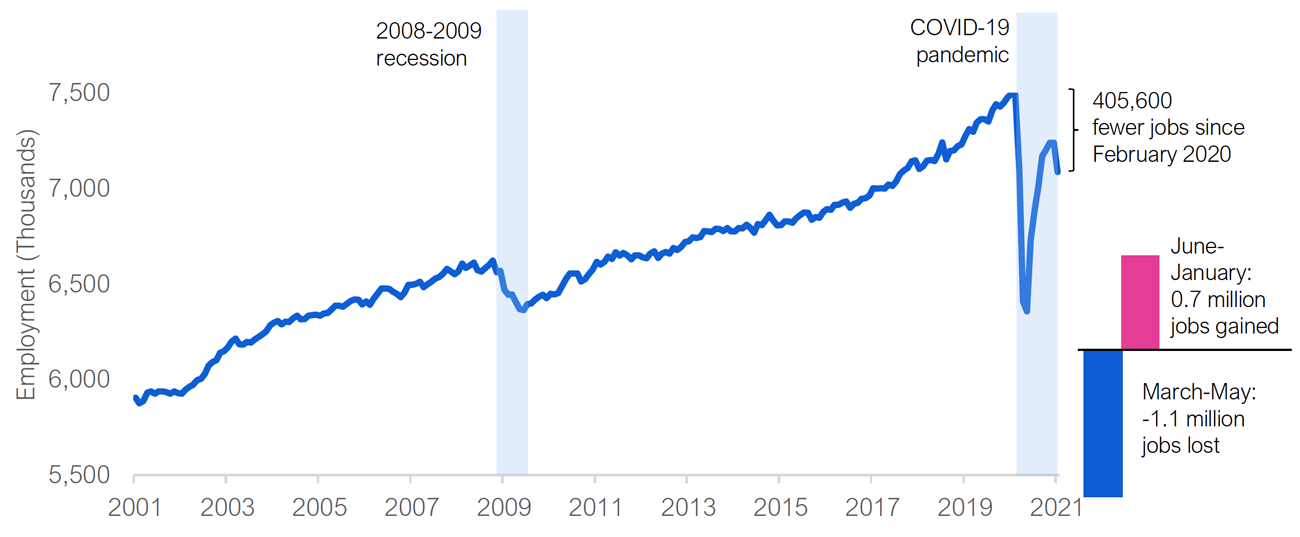

During the pandemic shutdowns, Ontario employment fell by a record 1.1 million jobs (or 15.2 per cent) from February to May 2020. As the economy reopened through last summer, employment rebounded strongly, rising by 729,100 since May 2020 and recovering almost two-thirds of the jobs lost during the first wave of the pandemic. Despite these gains, Ontario employment remained down by 405,600 jobs (or 5.4 per cent) in January 2021 compared to the pre-pandemic levels in February 2020.[5] The pace of monthly job gains has slowed noticeably as the second wave of COVID-19 infections and renewed partial restrictions caused job losses in some sectors in late 2020 and early 2021.

Figure 3‑5: Ontario’s employment still 405,600 jobs below pre-pandemic peak

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

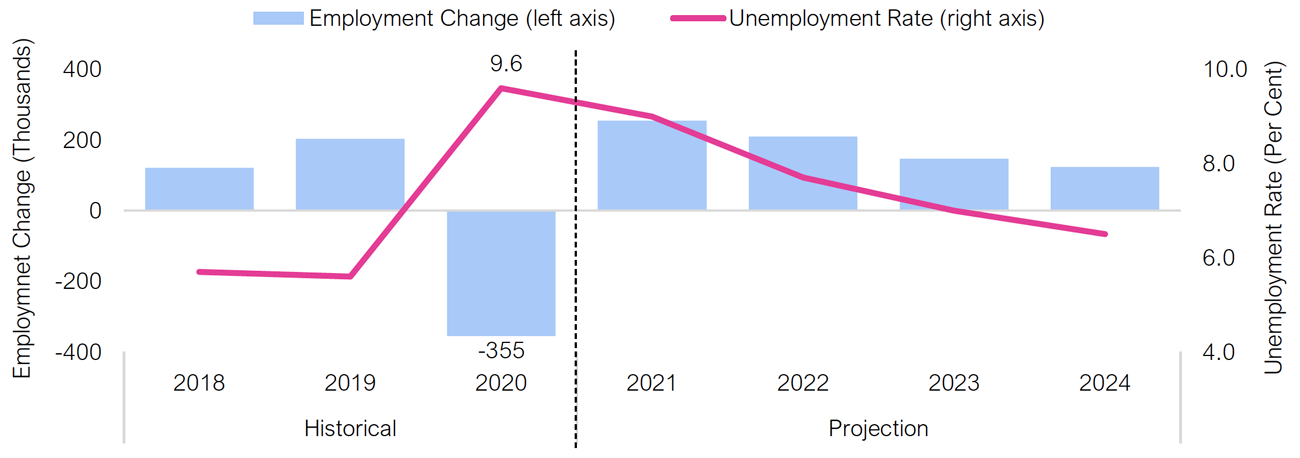

On an average annual basis, Ontario’s employment declined by 355,300 jobs (-4.8 per cent) in 2020, while the unemployment rate jumped to 9.6 per cent, up from 5.6 per cent in the previous year. As the economy improves through 2021, job growth will rebound, but the level of employment is not projected to reach its pre-pandemic peak until 2022. The unemployment rate will gradually trend down to pre-pandemic levels towards the end of the outlook.

Figure 3‑6: Unemployment rate to trend down to pre-pandemic levels

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

Source: Statistics Canada and FAO.

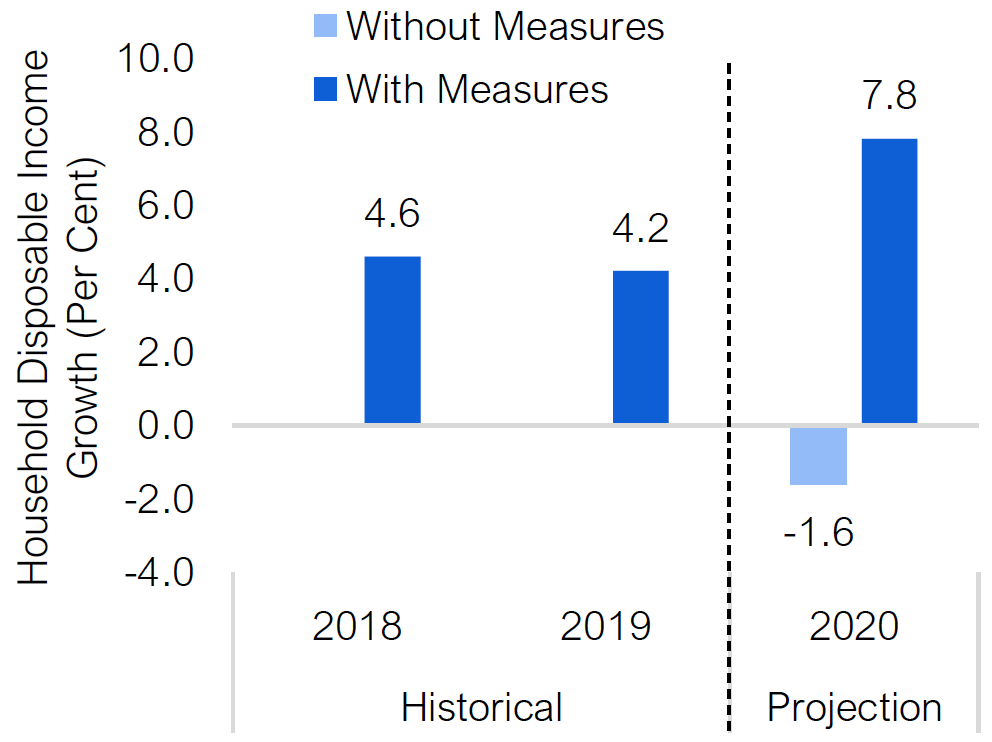

The sharp job losses during the pandemic have weakened labour income, which is projected to decline by 1.7 per cent in 2020. As employment prospects continue to improve, labour income growth is projected to rebound strongly in 2021, rising 4.8 per cent. In contrast, household disposable income is projected to increase by 7.8 per cent in 2020 reflecting significant support from the federal government. Without this support, household incomes would have declined by 1.6 per cent in 2020. Even with the conclusion of several income support programs in the past few months, household disposable income levels are expected to remain elevated over the outlook with the help of new recovery benefits.[6]

Corporate profits are projected to record a sharp 12.0 per cent decline in 2020, even as businesses adapted their operation to pandemic shutdown measures. Over the next two years, corporate profits are expected to recover strongly with average growth of 8.0 per cent as businesses increasingly return to more normal levels of activity. Overall, nominal GDP is expected to decline by 5.2 per cent in 2020, followed by a rebound of 5.4 and 6.0 per cent growth in 2021 and 2022, respectively.

Economic recovery faces heightened risks, including vaccine distribution

The path to economic recovery in 2021 will depend heavily on the success of the federal and provincial governments’ plans for vaccine distribution. The rapid development of multiple vaccines with promising early results provides a foundation for governments to achieve a successful immunization program. However, any combination of significant manufacturing setbacks, logistical challenges, or issues with public willingness could delay the governments’ planned schedule, resulting in slower economic growth. The economic performance in the near term will also be strongly influenced by the extent of COVID-19 restrictions. If heightened caseloads and capacity constraints in the health care system prompt the government to enact broader shutdowns, the economic recovery would be more muted.

In the medium term, the Ontario economy faces a number of material downside risks from potentially persistent structural changes. For example, consumer’s readiness to reengage in close-contact activities and international travel may be slow to recover to pre-pandemic levels even after social distancing measures are fully lifted. Some businesses may also restructure permanently as they scale back travel and office space requirements. As government emergency programs are gradually reduced, business and household insolvencies could rise, and recovery in many sectors could slow down. In addition, faced with much higher deficits and debt, governments may raise revenue or lower spending, slowing the pace of recovery further.

4 | Budget Outlook

Large ongoing budget deficits projected for Ontario

The FAO projects Ontario’s budget deficit will increase from $8.7 billion in 2019-20 to a record $35.5 billion in 2020-21. As the province recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic and the economy rebounds, the budget deficit is expected to remain elevated at $30.7 billion in 2021-22 and improve modestly to $24 billion in 2022-23. These projected deficits are broadly consistent with the government’s deficit forecast in the 2020 Ontario Budget.

Figure 4‑1: Ontario projected to have large ongoing budget deficits

Note: The FAO Winter 2021 Budget Balance is presented without the reserve.

Source: 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

Revenue outlook

Total revenues are projected to fall by $4.5 billion in 2020-21 to $151.6 billion, a decline of 2.9 per cent. The drop in revenues results from a substantial $10.3 billion (9.5 per cent) decline in tax revenues[7] and a $2.2 billion decrease in ‘other’ revenues, notably lower income from Government Business Enterprises[8]. These revenue declines are partially offset by a significant $8.0 billion (31.3 per cent) increase in transfers from the federal government, largely consisting of one-time COVID-related support.[9]

Figure 4‑2: Revenues expected to recover by 2022-23

Source: 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

Despite the expected recovery in economic activity in 2021 as COVID-19 vaccinations become more widely available, total revenues are projected to be largely unchanged at $152.1 billion in 2021-22. This reflects a decline in federal transfers to pre-pandemic levels, which almost offsets the $4.7 billion rebound in tax revenues and $2.1 billion increase in ‘other’ revenues.

As the economy is more fully reopened in 2022, revenues are projected to increase by a substantial $9.0 billion, reaching $161.1billion in 2022-23.

Expense outlook

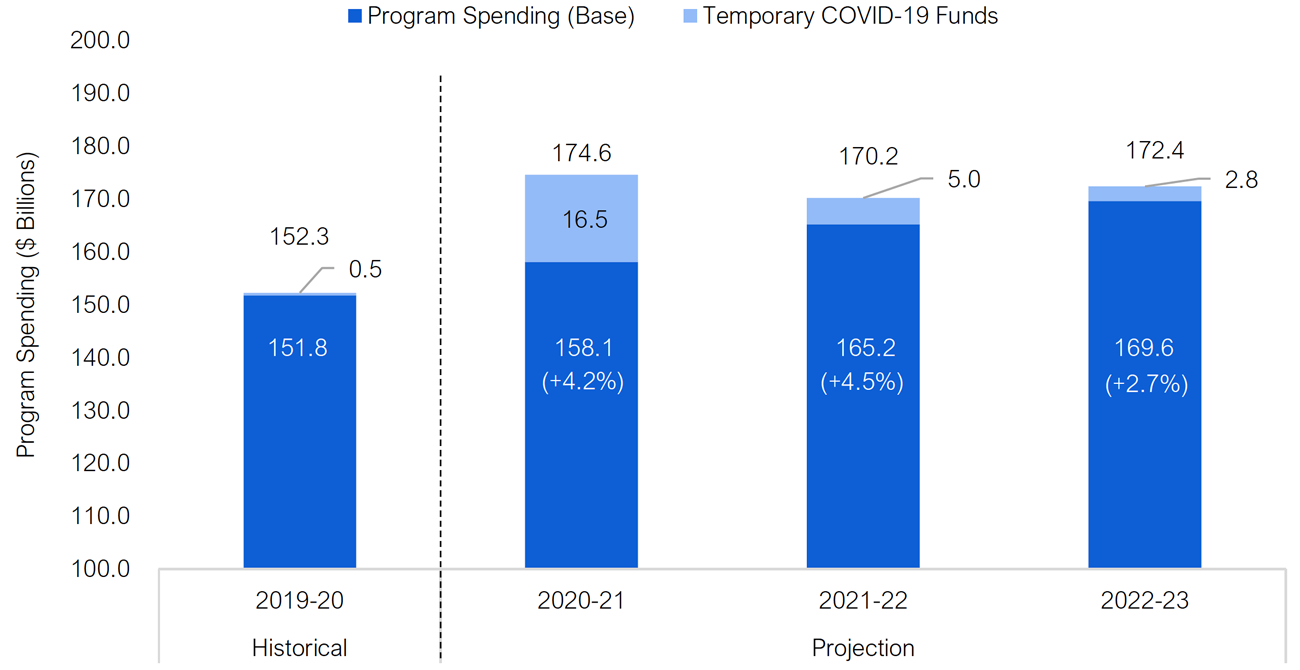

Based on the 2020 Budget spending plan, Ontario’s program spending in 2020-21 is projected to be $174.6 billion, or $22.3 billion higher than in 2019-20. This 14.7 per cent rise in program spending is the largest increase since 2009-10, with over 70 per cent of the total increase driven by temporary COVID-19 related spending.

Province plans to slow base program spending growth

Based on the 2020 Budget’s medium-term outlook, total program spending growth is projected to moderate over the 2021-22 to 2022-23 period as temporary COVID-19 related measures are gradually phased out. Specifically, COVID-19 related spending is projected to decline from $16.5 billion[10] in 2020-21 to $2.8 billion in 2022-23. Over this period, base program spending growth (excluding COVID-related expenditures) is projected to slow from 4.2 per cent in 2020-21 to 2.7 per cent in 2022-23.

Figure 4‑3: Program spending growth is projected to moderate over the medium term as pandemic eases

Note: The numbers in parentheses represent the annual growth in base program spending.

Source: 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

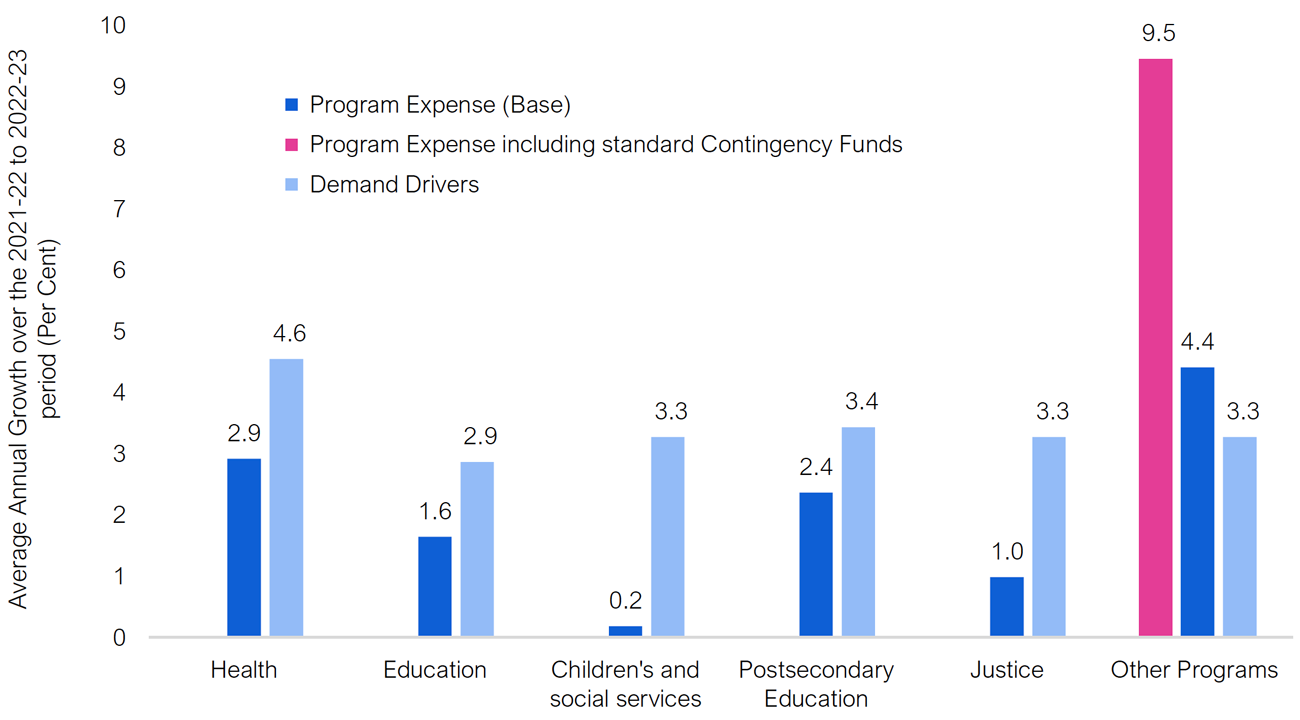

Program spending growth in key sectors will not keep pace with demand for public services

Since COVID-19 related spending has temporarily inflated the government’s program spending, the FAO has divided each sector’s spending into ‘base program spending’ and ‘temporary COVID-19 funds’ to identify the underlying trend for regular or ‘base’ program spending. Based on the 2020 Budget, over the next two years planned program spending growth in key sectors will not keep pace with the underlying growth in the demand for public services, which is driven by factors such as population growth and price inflation (Figure 4-4).

In the health sector, base spending is projected to grow at an average annual pace of 2.9 per cent, below the projected growth of 4.6 per cent in key cost drivers of the health care sector, such as health inflation, population growth and aging. Education sector spending is projected to grow at an average annual pace of 1.6 per cent, slower than the 2.9 per cent annual growth projected for the number of school-age children and price inflation. Similarly, planned program spending growth in children’s and social services, justice, and postsecondary education sectors will be below the average projected growth in their underlying demand drivers over the 2021-22 to 2022-23 period.

Figure 4‑4: Base program expense growth in key sectors will not keep pace with demand drivers*

Note: The average annual growth rates over the 2021-22 to 2022-23 period in different sectors refer to base program spending and do not include any COVID-19 related spending.

* Demand drivers reflect factors such as population growth, aging and consumer price inflation.

Source: 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

Growth in ‘Other Programs’ spending driven by significant increase to standard contingency funds

‘Other Programs’ includes a variety of ministries[11] along with the standard operating and capital contingency funds, which are regular prudence measures incorporated into the government’s budget. According to the 2020 Budget, the government allocated $3.0 billion for its standard contingency funds in 2020-21,[12] significantly above the usual size of the funds,[13] and also in addition to the dedicated COVID-19 contingency funds. While the standard contingency funds are maintained to manage expense risks, the government has yet to indicate the specific purpose of the sharp increase in these funds. Importantly, if these contingency funds are not used for new initiatives or to respond to future extraordinary events, the unused portion of the funds would be available to reduce future deficits.[14]

Over the 2021-22 to 2022-23 period, the allocation to these standard contingency funds will increase even further, accelerating the growth in ‘Other Program’ spending to an average annual pace of 9.5 per cent, significantly higher than the planned growth in all the key sectors. Excluding contingency funds, ‘other’ base program spending is projected to grow at 4.4 per cent annually, 1.1 percentage point above the pace of population growth and inflation.

Budget deficit

The FAO projects a record budget deficit of $35.5 billion (or 4.2 per cent of GDP) in 2020-21, as the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in both a sharp decline in revenues and a significant increase in program spending. Importantly, the government could report a smaller budget deficit for 2020-21 than the FAO’s projection if it does not allocate the remaining contingency funds to specific programs or spends less than planned.[15]

Figure 4‑5: Ontario projected to record large ongoing budget deficits

Budget Balance is presented without the reserve.

Source: 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

As the province recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic and the economy rebounds, the budget deficit is expected to remain elevated at $30.7 billion in 2021-22 and improve modestly to $24.0 billion in 2022-23. These projected deficits are broadly consistent with the government’s deficit forecast in the 2020 Ontario Budget.

Debt outlook

Net debt is expected to rise sharply by $41.7 billion, to $395 billion in 2020-21. The substantial increase in net debt results in a large jump in the net debt-to-GDP ratio, which is expected to rise to 46.7 per cent in 2020-21. Large and continued deficits lead to increasing levels of debt and a rising net debt-to-GDP ratio over the outlook, which reaches almost 50 per cent by 2022-23 – about 10 percentage points higher than the pre-pandemic ratio.

Figure 4‑6: Net debt-to-GDP ratio increases substantially in 2020-21

Source: Statistics Canada, Ontario Public Accounts and FAO.

Despite the substantial increase in debt, low borrowing rates are expected to limit the rise in interest on debt payments over the outlook. By 2022-23, interest on debt is projected to reach $12.7 billion, just $254 million higher than in 2019-20.

As a share of revenue, interest on debt is expected to rise to 8.2 per cent in 2020-21, as revenues decline because of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as revenues rebound, interest payments as a share of revenues are expected to decline to 7.9 per cent by 2022-23, similar to the pre-pandemic share.

Figure 4‑7: Interest on debt payments to remain largely unchanged over the projection period

Source: Ontario Public Accounts and FAO.

Ontario’s fiscal recovery plan

In Ontario, the Fiscal Sustainability, Transparency and Accountability Act, 2019 (FSTAA) requires that when the budget is in deficit, the Province must develop a fiscal recovery plan that specifies how the budget will be balanced and the time period over which this will be achieved. The government has committed to present a multi-year fiscal recovery plan in the 2021 Ontario budget, to be delivered by March 31, 2021.

To illustrate the implications of balancing the budget in the current fiscal environment, the FAO extended its base case projection to 2025-26. Figure 4‑8 shows the FAO’s extended outlook for the deficit, which is projected to improve gradually from $30.7 billion in 2021-22 to roughly $17 billion by 2023-24.

In the absence of policy changes, the FAO projects Ontario’s budget deficits to remain steady in the range of $16 billion in the extended projection. These ongoing deficits reflect the starting point of an $8.7 billion deficit in 2019-20 (before the onset of the COVID-19 crisis), the lasting economic and fiscal impacts of the pandemic going forward, as well as the province’s aging population, which contributes to both slower economic growth and higher demands for government spending.

Figure 4‑8: $16 billion adjustment is required to balance Ontario’s budget by 2025-26

Note: Budget Balance is presented before the reserve.

Source: Ontario Public Accounts and FAO.

To provide an estimate of the extent of ongoing revenue increases or spending cuts that would be required to balance the budget, the FAO constructed a hypothetical scenario under which the budget is balanced over a five-year period. In this “balanced budget scenario,” a total of $16 billion of revenue increases and spending cuts (in equal measure) are phased in over five years to reach a balanced budget by 2025-26.

To illustrate the policy tools available to the government to achieve these fiscal adjustments, the FAO estimated the sensitivity of the budget balance to changes in three key policy areas: tax revenues, federal transfers, and program expenditures. Table 4‑1 provides estimates of both the immediate impact in 2021-22 as well as the longer-term budget impact in 2025-26 of various policy changes.

Change in budget balance in:

Change Beginning in 2021-22

2021-22

2025-26

Tax Policy

A sustained 10 per cent increase in Personal Income Tax revenues ($500 per tax filer in 2019-20) over the projection

+$3.7 billion

+$4.9 billion

A sustained 1 percentage point increase in Corporations Tax rates over the projection[16]

+$0.8 billion

+$1.2 billion

A sustained 1 percentage point increase in the HST rate over the projection

+$3.6 billion

+$4.7 billion

Federal Transfers

A sustained 1 percentage point increase in the annual growth of the Canada Health Transfer over the projection

+$0.2 billion

+$1.0 billion

A sustained 1 percentage point increase in the annual growth of the Canada Social Transfer over the projection

+$0.1 billion

+$0.5 billion

Expenditure Policy

A sustained 0.5 percentage point decrease in the growth rate of total program spending over the projection

+$0.9 billion

+$4.7 billion

A sustained 1 percentage point decrease in the growth rate of health spending over the projection

+$0.7 billion

+$4.2 billion

Source: FAO.

If the government were to permanently increase personal income tax revenue by 10 per cent or around $500 per tax filer, starting in 2021-22, the budget deficit would improve by $3.7 billion in the first year and by $4.9 billion by 2025-26.

For federal transfers, if the annual growth rate of the Canada Health Transfer or the Canada Social Transfer were to increase by 1 percentage point over the projection, the budget deficit would decrease by 1.0 billion or $0.5 billion respectively by 2025-26.

For expenditure policy, if the government were to decrease the growth rate of program spending by 0.5 percentage points in each year beginning in 2021-22, the budget deficit would decrease by $4.7 billion by 2025-26.

Given the FSTAA requirements for a balanced budget, these estimated budget sensitivities are intended to inform the debate around the government’s policy choices.

Fiscal sustainability

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused deficits and debt to rise to record levels around the world, raising concerns about the ability of governments to finance the higher debt burdens while continuing to provide public services. This has led to an active debate about fiscal sustainability, including the unique challenges for subnational jurisdictions like Ontario.[17]

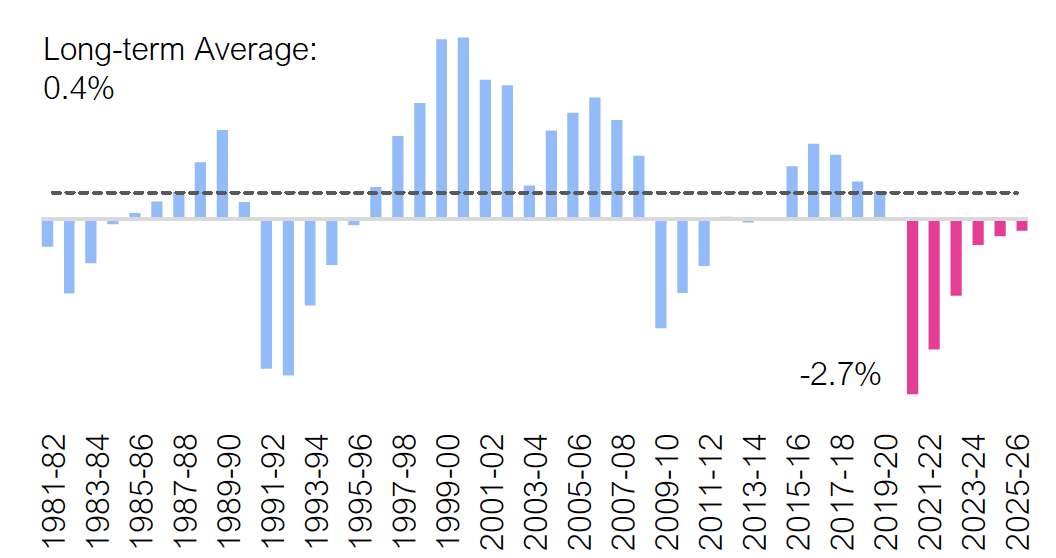

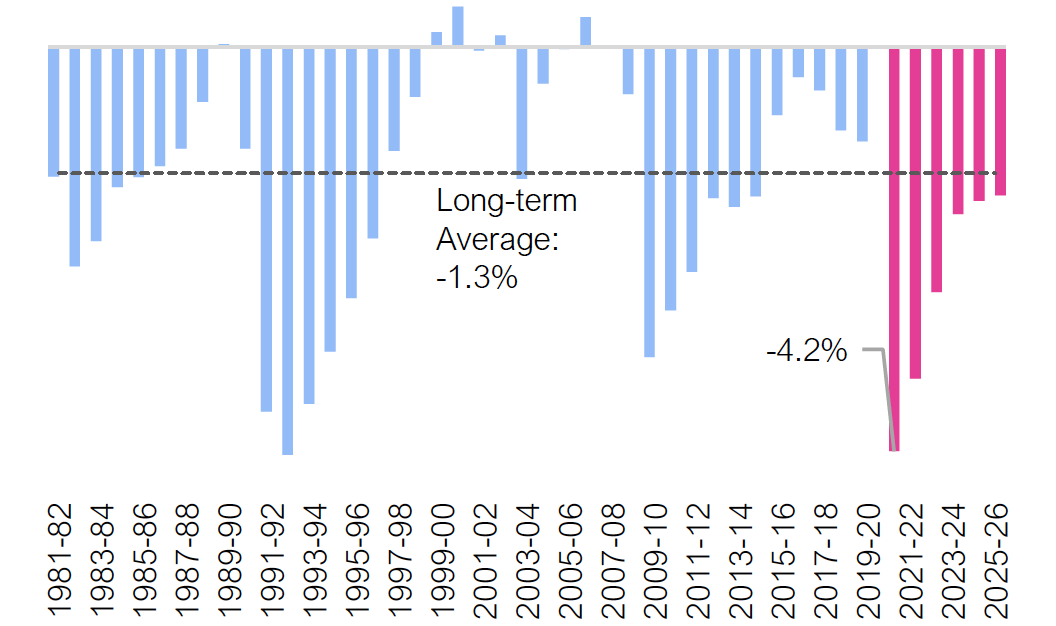

Several key indicators are often used to assess the state of a government’s finances, including the primary budget balance, the overall budget balance, the net debt-to-GDP ratio and interest on debt as a share of revenue. Figure 4-9 presents trends in these key indicators historically and over the FAO’s extended projection horizon.

While most of the key fiscal indicators experienced a sharp deterioration in 2020-21, the expected economic recovery will contribute to improvements in some of these fiscal measures over the forecast period. Based on the FAO’s projections, the cost of financing the large increase in provincial debt is expected to be manageable over the medium term. Importantly, this conclusion is largely due to the assumption that interest rates remain near historical lows over the outlook. Even so, the province’s net debt as a share of GDP is projected to increase continuously over the extended projection, making the province more vulnerable to unexpected increases in interest rates in the future.

Figure 4‑9: Trends in key deficit and debt indicators for Ontario

Primary Budget Balance as a share of GDP

- The primary budget balance measures the extent to which program spending is being funded from current revenues and shows the component of public finances most under the control of the government.

- Historically averaged a surplus of 0.4 per cent of the province’s GDP.

- Projected to deteriorate to a deficit of -2.7 per cent of GDP in 2020-21 – improves over the projection but remains below the historical average.

Overall Budget Balance as a share of GDP

- The overall budget balance measures the extent to which the government needs to borrow to cover its program expense and interest payments. Under FSTAA, the government is required to release a plan for an overall balanced budget if in deficit.

- Historically averaged a deficit of -1.3 per cent of GDP, deteriorating during economic downturns and improving in recoveries.

- Projected to fall to a deficit of -4.2 per cent in 2020-21 – improves over the projection but remains below the historical average.

Net Debt as a share of GDP

- Net debt as a share of GDP indicates the ability of the government to raise funds to repay its debt obligations. Under FSTAA, the government is required to present a debt burden reduction strategy in its annual budget.

- Historically averaged 26.8 per cent of GDP, but has progressively increased over the past four decades, rising noticeably during economic downturns.

- Projected to reach a record 46.7 per cent in 2020-21 and rise to 50.9 per cent by 2025-26.

Interest on Debt as a share of revenue

- The ratio of interest on debt-to-revenue indicates budgetary flexibility – a higher ratio indicates that the government has less revenue available to spend on key programs such as health care or education.

- Historically averaged 10.3 per cent of revenues.

- Projected to remain relatively stable at 8.2 per cent in 2020-21 and over the projection.

Source: Ontario Economic Accounts, Ontario Public Accounts, 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

5 | Appendix

Appendix A: Economic Tables

(Per Cent Growth)

2018a

2019a

2020f

2021f

2022f

2023f

2024f

Nominal GDP

FAO - Winter 2021

4.1

3.8

-5.2

5.4

6.0

3.7

3.4

2020 Ontario Budget*

4.1

3.8

-5.0

6.6

5.7

4.2

-

Consensus**

4.1

3.8

-4.7

6.7

6.6

4.5

-

Labour Income

FAO - Winter 2021

6.1

4.6

-1.7

4.8

5.3

3.6

3.3

2020 Ontario Budget

6.1

4.6

-2.5

5.3

5.1

4.6

-

Corporate Profits

FAO - Winter 2021

0.6

0.0

-12.0

7.9

8.2

4.3

3.7

2020 Ontario Budget

0.6

0.0

-16.0

10.0

10.3

2.7

-

Household Consumption

FAO - Winter 2021

4.7

3.5

-6.3

6.4

6.5

3.9

3.6

2020 Ontario Budget

4.7

3.5

-6.0

7.4

6.0

4.2

-

* Ministry of Finance forecast released in the 2020 Ontario Budget was based on information available up to October 2, 2020.

** Composed of private-sector banks and forecasters. Forecasts as of January 25, 2021.

Source: Ontario Economic Accounts, 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

(Per Cent Growth)

2018a

2019a

2020f

2021f

2022f

2023f

2024f

Real GDP

FAO - Winter 2021

2.8

2.1

-5.9

3.9

4.5

2.0

1.7

2020 Ontario Budget

2.8

1.7

-6.5

4.9

3.5

2.0

-

Consensus**

2.8

1.7

-5.9

4.6

4.3

2.1

-

Real GDP Components

Household Consumption

2.9

1.9

-6.5

3.8

4.3

1.8

1.6

Residential Investment

-3.6

0.5

8.0

11.0

3.3

2.3

1.8

Business Investment

13.2

-2.6

-14.1

2.4

5.1

1.8

1.6

Government (Consumption and Investment)

4.3

1.3

-0.2

4.7

2.0

2.0

2.0

Exports

1.1

2.1

-8.3

6.8

4.8

2.2

1.7

Imports

2.3

0.6

-9.6

7.1

4.3

2.1

1.7

* Ministry of Finance forecast released in the 2020 Ontario Budget was based on information available up to October 2, 2020.

** Composed of private-sector banks and forecasters. Forecasts as of January 25, 2021.

Source: Ontario Economic Accounts, 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

(Per Cent Growth)

2018a

2019a

2020f

2021f

2022f

2023f

2024f

Employment

FAO - Winter 2021

1.7

2.8

-4.8

3.6

2.9

1.9

1.6

2020 Ontario Budget*

1.7

2.8

-5.4

5.0

2.5

1.9

-

Unemployment Rate (Per Cent)

FAO - Winter 2021

5.7

5.6

9.6

9.0

7.7

7.0

6.5

2020 Ontario Budget

5.7

5.6

9.5

7.7

6.8

6.3

-

Labour Force

FAO - Winter 2021

1.4

2.7

-0.6

2.9

1.4

1.2

1.0

2020 Ontario Budget

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

CPI Inflation (Per Cent)

FAO - Winter 2021

2.4

1.9

0.7

1.9

2.0

2.0

2.0

2020 Ontario Budget

2.4

1.9

0.5

1.7

2.0

1.9

-

Canada Real GDP

FAO - Winter 2021

2.4

1.9

-5.7

3.7

4.5

2.0

1.7

2020 Ontario Budget

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

U.S. Real GDP

FAO - Winter 2021

3.0

2.2

-3.5

4.0

3.3

2.3

1.9

2020 Ontario Budget

3.0

2.2

-4.0

3.9

2.9

2.3

-

Canadian Dollar (Cents US)

FAO - Winter 2021

77.2

75.4

74.6

77.3

77.9

78.2

78.4

2020 Ontario Budget

77.2

75.4

74.2

75.3

75.4

76.0

-

Three-month Treasury Bill Rate (Per Cent)

FAO - Winter 2021

1.4

1.7

0.4

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.7

2020 Ontario Budget

1.4

1.7

0.4

0.2

0.2

0.4

-

10-year Government Bond Rate (Per Cent)

FAO - Winter 2021

2.3

1.6

0.7

0.6

1.1

1.3

1.7

2020 Ontario Budget

2.3

1.6

0.7

0.8

1.3

1.7

-

* Ministry of Finance forecast released in the 2020 Ontario Budget was based on information available up to October 2, 2020.

Source: Statistics Canada, 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

Appendix B: Fiscal Tables

($ Billions)

2017-18a

2018-19a

2019-20a

2020-21f

2021-22f

2022-23f

Revenue

Personal Income Tax

32.9

35.4

37.7

37.2

36.5

38.8

Sales Tax

25.9

27.8

28.6

26.7

28.9

31.0

Corporations Tax

15.6

16.6

15.4

8.3

10.5

11.2

All Other Taxes

25.3

25.7

26.5

25.8

26.7

27.9

Total Taxation Revenue

99.7

105.5

108.3

97.9

102.7

108.9

Transfers from Government of Canada

24.9

25.1

25.4

33.4

27.1

27.6

Income from Government Business Enterprises

6.2

5.5

5.9

3.6

4.9

6.4

Other Non-Tax Revenue

16.3

16.3

16.5

16.7

17.5

18.2

Total Revenue

150.6

153.7

156.1

151.6

152.1

161.1

Expense

Health Sector

59.1

61.9

63.7

73.0

71.0

70.5

Health (Base)

63.7

64.6

67.0

68.5

Temporary COVID-19 Funds

0.0

8.3

4.0

2.0

Education Sector

27.3

28.7

30.2

31.0

31.1

31.3

Education (Base)

29.8

30.3

31.1

31.3

Temporary COVID-19 Funds

0.4

0.8

0.0

0.0

Children's and Social Services Sector

16.3

16.8

17.1

17.9

17.8

17.9

Children’s and Social Services (Base)

17.1

17.9

17.8

17.9

Temporary COVID-19 Funds

0.0

0.1

0.0

0.0

Postsecondary Education Sector

10.5

11.2

10.5

10.7

10.9

11.2

Justice Sector

4.3

4.5

4.7

4.6

4.6

4.6

Justice (Base)

4.7

4.6

4.6

4.6

Temporary COVID-19 Funds

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

Other Programs

24.9

25.6

26.0

37.4

34.8

36.9

Other*(Base)

26.0

30.1

33.8

36.1

Temporary COVID-19 Funds

0.1

7.3

1.0

0.8

Total Program Expense

142.4

148.8

152.3

174.6

170.2

172.4

Total Program Expense (Base)

151.8

158.1

165.2

169.6

Total Temporary COVID-19 Funds

0.5

16.5

5.0

2.8

Interest on Debt

11.9

12.4

12.5

12.5

12.5

12.7

Total Expense

154.3

161.1

164.8

187.1

182.7

185.1

Budget Balance**

-3.7

-7.4

-8.7

-35.5

-30.7

-24.0

* Includes Teachers’ Pension Plan.

** Budget Balance is presented without reserve.

Numbers may not add due to rounding.

Source: Statistics Canada, Ontario Economic Accounts, Ontario Public Accounts, 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

($ Billions)

2017-18a

2018-19a

2019-20a

2020-21f

2021-22f

2022-23f

Budget Balance*

-3.7

-7.4

-8.7

-35.5

-30.7

-24.0

Accumulated Deficit

209.0

216.6

225.8

261.3

291.9

316.0

Net Debt

323.8

338.5

353.3

395.0

432.4

463.4

Net Debt to GDP (Per Cent)

39.3

39.4

39.6

46.7

48.5

49.1

* Budget Balance is presented without reserve.

Numbers may not add due to rounding.

Source: Statistics Canada, Ontario Economic Accounts, Ontario Public Accounts, 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

Appendix C: Extended Outlook

Historical

FAO Projection

FAO Extended Projection

($ Billions)

2018-19a

2019-20a

2020-21f

2021-22f

2022-23f

2023-24f

2024-25f

2025-26f

Revenue

153.7

156.1

151.6

152.1

161.1

166.7

172.2

177.9

Total Program Expense

148.8

152.3

174.6

170.2

172.4

170.7

174.9

179.8

Interest on Debt

12.4

12.5

12.5

12.5

12.7

13.0

13.4

14.2

Interest on Debt as a Share of Revenue (Per Cent)

8.1

8.0

8.2

8.2

7.9

7.8

7.8

8.0

Total Expense

161.1

164.8

187.1

182.7

185.1

183.7

188.4

194.0

Budget Balance*

-7.4

-8.7

-35.5

-30.7

-24.0

-17.0

-16.1

-16.1

Net Debt

338.5

353.3

395.0

432.4

463.4

486.8

510.1

533.1

Net Debt to GDP (Per Cent)

39.4

39.6

46.7

48.5

49.1

49.7

50.3

50.9

* Budget Balance is presented without reserve.

Numbers may not add due to rounding.

Source: Statistics Canada, Ontario Economic Accounts, Ontario Public Accounts, 2020 Ontario Budget and FAO.

About this document

Established by the Financial Accountability Officer Act, 2013, the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) provides independent analysis on the state of the Province’s finances, trends in the provincial economy and related matters important to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario.

This report was prepared by Sabrina Afroz, Edward Crummey, Zohra Jamasi, Jay Park, Nicolas Rhodes and Mavis Yang, under the direction of Paul Lewis and David West. External reviewers were provided with earlier drafts of this report for their comments. However, the input of external reviewers implies no responsibility for this final report, which rests solely with the FAO.

The content of this report is based on information available to February 5, 2021. Background data used in this report are available upon request.

In keeping with the FAO’s mandate to provide the Legislative Assembly of Ontario with independent economic and financial analysis, this report makes no policy recommendations.

FAO’s Fiscal Projections

The FAO forecasts provincial finances based on projections of existing and announced revenue and spending policies. The FAO’s tax revenue projections are based on an assessment of the outlook for the provincial economy and current tax policies. Given the government’s discretion over spending, the FAO adopts the government’s announced spending plans from fiscal documents and incorporates policy announcements as appropriate. All average annual growth rates in this report are calculated using the year before the first indicated year as the base.

Graphic Descriptions

Historical

Projection

Ontario Real GDP Growth (Per Cent)

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

2.8

2.1

-5.2

3.9

4.5

2.0

1.7

Historical

Projection

Extended Projection

Budget Balance ($ Billions)

2018-19

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

2022-23

2023-24

2024-25

2025-26

Historical

-7.4

-8.7

FAO Winter 2021 Update

-35.5

-30.7

-24.0

-17.0

-16.1

-16.1

Interest on Debt

($ Billions)

Interest on Debt to Revenue

(Per Cent)

Historical

2013-14

11.2

9.1

2014-15

11.2

8.9

2015-16

11.6

8.5

2016-17

11.7

8.3

2017-18

11.9

7.9

2018-19

12.4

8.1

2019-20

12.5

8.0

Projection

2020-21

12.5

8.2

2021-22

12.5

8.2

2022-23

12.7

7.9

Historical

Projection

Ontario GDP Growth (Per Cent)

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

Real

2.8

2.1

-5.2

3.9

4.5

2.0

1.7

Nominal

4.1

3.8

-5.9

5.4

6.0

3.7

3.4

Real GDP Growth (Per Cent)

World

Advanced Economies

Emerging Market and Developing Economies

Historical

2007

5.5

2.7

8.4

2008

3.0

0.2

5.7

2009

-0.1

-3.3

2.8

2010

5.4

3.1

7.4

2011

4.3

1.8

6.4

2012

3.5

1.2

5.4

2013

3.5

1.4

5.1

2014

3.5

2.1

4.7

2015

3.4

2.4

4.3

2016

3.3

1.8

4.5

2017

3.8

2.5

4.8

2018

3.5

2.2

4.5

2019

2.8

1.7

3.7

Projection

2020

-3.5

-4.9

-2.4

2021

5.5

4.3

6.3

2022

4.2

3.1

5.0

Historical

Projection

(Per Cent)

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

3-month Treasury Bill Yield

1.4

1.7

0.4

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.7

10-year Government of Canada Bond Yield

2.3

1.6

0.7

0.7

1.2

1.4

1.8

Real GDP ($2012 chained millions)

Historical

Projection

Historical

2019Q3

801556

2019Q4

802562

2020Q1

788118

2020Q2

692071

2020Q3

757172

Projection

2020Q4

766536

2021Q1

763369

2021Q2

772797

2021Q3

786755

2021Q4

797687

2022 Q1

807321

2022 Q2

814410

2022 Q3

818262

2022 Q4

822353

2023 Q1

826109

2023 Q2

829916

2023 Q3

833687

2023 Q4

837655

Thousands

Pre-pandemic peak employment

7,494.1

February to May 2020 change in employment

-1,134.7

June to December 2020 change in employment

882.6

Total change in employment since February

-252.1

Historical

Projection

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

Employment Change (Thousands)

120.8

203.6

-355.3

254.4

209.8

146.6

123.8

Unemployment Rate (Per Cent)

5.7

5.6

9.6

9.0

7.7

7.0

6.5

Historical

Projection

Household Disposable Income Growth (Per Cent)

2018

2019

2020

Without Measures

-1.6

With Measures

4.6

4.2

7.8

Historical

Projection

Budget Balance ($ Billions)

2017-18

2018-19

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

2022-23

Historical

-3.7

-7.4

-8.7

2020 Ontario Budget

-36.0

-31.1

-26.2

Reserve

-2.5

-2.0

-2.0

FAO Winter 2021 Update

-35.5

-30.7

-24.0

Change in Revenue ($ Billions)

2020-21

2021-22

Tax Revenue

-10.3

4.7

Federal Transfers

8.0

-6.3

Other Revenue

-2.2

2.1

Total

-4.5

0.5

Historical

Projection

Total Revenue ($Billions)

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

2022-23

156.1

151.6

152.1

161.1

Historical

Projection

Program Spending

($ Billions)

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

2022-23

Total Program Spending

152.3

174.6

170.2

172.4

Program Spending (Base)

151.8

158.1

165.2

169.6

Growth in Base Program Spending

4.2%

4.5%

2.7%

Temporary COVID-19 Funds

0.5

16.5

5.0

2.8

Average annual growth over the 2021-22 to 2022-23 period (Per Cent)

Program Expense (Base)

Program Expense including standard Contingency Funds

Demand Drivers

Health

2.9

4.6

Education

1.6

2.9

Children's and social services

0.2

3.3

Postsecondary Education

2.4

3.4

Justice

1.0

3.3

Other Programs

4.4

9.5

3.3

Historical

Projection

Budget Balance ($ Billions)

2017-18

2018-19

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

2022-23

Historical

-3.7

-7.4

-8.7

2020 Ontario Budget

9.9%

-36.0

-31.1

-26.2

Reserve

9.9%

-2.5

-2.0

-2.0

FAO Winter 2021 Update

9.9%

-35.5

-30.7

-24.0

Net Debt

($ Billions)

Net Debt to GDP Ratio

(Per Cent)

Historical

2013-14

276.2

39.7

2014-15

294.6

40.5

2015-16

306.4

40.3

2016-17

314.1

39.7

2017-18

323.8

39.3

2018-19

338.5

39.4

2019-20

353.3

39.6

Projection

2020-21

395.0

46.7

2021-22

432.4

48.5

2022-23

463.4

49.1

Interest on Debt

($ Billions)

Interest on Debt to Revenue

(Per Cent)

Historical

2013-14

11.2

9.1

2014-15

11.2

8.9

2015-16

11.6

8.5

2016-17

11.7

8.3

2017-18

11.9

7.9

2018-19

12.4

8.1

2019-20

12.5

8.0

Projection

2020-21

12.5

8.2

2021-22

12.5

8.2

2022-23

12.7

7.9

Historical

Projection

Extended Projection

Budget Balance ($ Billions)

2018-19

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

2022-23

2023-24

2024-25

2025-26

Historical

-7.4

-8.7

FAO Winter 2021 Update

-35.5

-30.7

-24.0

-17.0

-16.1

-16.1

FAO Balanced Budget Scenario

-28.1

-18.8

-8.4

-4.0

-0.1

(Per Cent)

Long-term Average

2020-21

Primary Budget Balance as a share of GDP

0.4

-2.7

Overall Budget Balance as a share of GDP

-1.3

-4.2

Net Debt as a share of GDP

26.8

46.7

Interest on Debt as a share of GDP

10.3

8.2

Footnotes

[1] Based on Statistics Canada’s Provincial Economic Accounts, which cover the period 1981 to 2019.

[2] According to federal health authorities, current vaccination plans are to cover the majority of the Canadian population by the end of 2021. Social distancing and select restrictions are assumed to remain in place throughout the immunization period and taper off afterwards.

[3] Based on Statistics Canada’s Provincial Economic Accounts which cover the period 1981 to 2019.

[4] According to federal health authorities, current vaccination plans are to cover the majority of the Canadian population by the end of 2021. Social distancing and select restrictions are assumed to remain in place throughout the immunization period and taper off afterwards.

[5] The FAO will release its annual report on employment in early 2021 with details of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on jobs.

[6] New recovery benefits supporting households include Canada Recovery Benefit, Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit, Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit, and Temporary Enhancements to Employment Insurance, among others.

[7] The three largest sources of tax revenue – Corporations Tax (-$7.1 billion), Sales Tax (-$1.9 billion) and Personal Income Tax (-$0.6 billion) – make up most of the overall decline.

[8] This is largely the result of a sharp drop in Ontario Lottery and Gaming Commission revenues from $2,309 million in 2019-20 to $200 million in 2020-21, reflecting the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns.

[9] Roughly $7 billion of the increase in federal transfers is one-time COVID-19 pandemic support. See page 178 of the 2020 Ontario Budget.

[10] For a sectoral breakdown of the $16.5 billion COVID-19 spending, see Appendix Table 5-4. The FAO will update this estimate in the coming months.

[11] The ministries include Transportation; Energy, Norther Development and Mines; Finance; Treasury Board Secretariat; Municipal Affairs and Housing; Government and Consumer Services; Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries; Labour, Training and Skills Development; Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs; Infrastructure; Economic Development, Job Creation and Trade; Environment, Conservation and Parks; Natural Resources and Forestry; Board of Internal Economy; Seniors and Accessibility; Indigenous Affairs; Executive Offices; and Francophone Affairs. In 2019-20, other programs represented 17.1 per cent of total program spending. However, over the 2020-21 to 2022-23 period, the share of other programs in total program spending will rise to 21.1 per cent on average.

[12] See Table 3.13 in the 2020 Ontario Budget.

[13] For example, in the 2019 Ontario Budget, the government allocated $1.1 billion to the standard contingency funds. See Table 3.13 in the 2019 Ontario Budget for details.

[14] The government committed to using any remaining contingency funds at year end to reduce Ontario’s net debt position. See page 176 of the 2020 Ontario Budget.

[15] The FAO will update the estimate of the unallocated funds in the Expenditure Monitor report in coming months.

[16] The increase in the general Corporations Tax rate also incorporates increases to Manufacturing and Processing Corporations Income Tax Rate and the Small Business Corporations Income Tax rate.

[17] Fiscal sustainability is a long-term concept that depends on many factors, including the pace of population and economic growth, interest rates and the fiscal policies adopted by the government. Prior to the pandemic, in the 2020 Long-Term Budget Outlook the FAO highlighted that if the Ontario government was able to successfully transform public services and achieve permanent cost savings, this would result in a steady improvement in Ontario’s fiscal position over the long term. The report also noted that permanent cost savings have been difficult for governments to achieve historically.