Key Points

- At the request of the Standing Committee on Finance and Economic Affairs, the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) has prepared a report to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on insolvencies in Ontario.

- Following steady declines after the 2008-09 recession, insolvencies in Ontario began rising in 2018, reaching a seven-year peak in 2019.[1] The increase in insolvencies can mostly be attributed to the impact of rising interest rates on the financial position of households, which had accumulated a record amount of debt relative to income.

- Despite the economic damage the COVID-19 pandemic caused to households and businesses, insolvencies in Ontario declined sharply by 24.0 per cent in 2020 to the lowest annual level since 2000.

- The significant drop in insolvencies in 2020 is exceptional among recessionary periods and reflects a number of unique temporary factors related to the pandemic. Lower interest rates helped reduce debt payment obligations and some households took advantage of debt payment deferrals offered by creditors. As well, federal government measures provided significant income support, which helped the financial position of Ontario households and businesses during the pandemic.

- Insolvencies declined in all Ontario major cities and across most industries in 2020. However, insolvencies increased in three industries: educational services; information, culture and recreation; and real estate.

- Total insolvencies fell in all Canadian provinces in 2020, with the Atlantic provinces generally registering the largest declines. Ontario reported the third-smallest rate of decline of total insolvencies in 2020 behind Alberta and Manitoba.

- Given the ongoing economic challenges related to the pandemic, insolvencies could increase over the medium term and will depend in part on the extent and pace at which government income support is phased out. As well, interest rates are expected to rise gradually, which will put upward pressure on debt obligations for Ontario households. Many businesses, particularly those most affected by the pandemic shutdowns, have indicated they are unable to take on additional debt and might need to consider closure or bankruptcy.

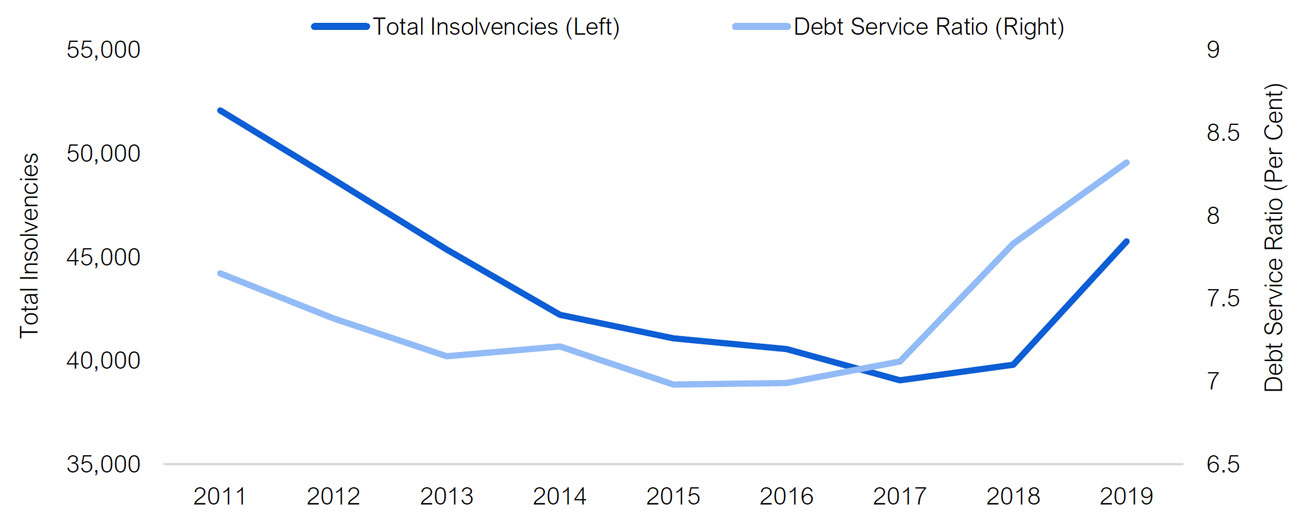

Insolvencies were rising before the pandemic

Following steady declines after the 2008-09 recession, Ontario consumer and business insolvencies increased by 1.9 per cent in 2018 and 15.0 per cent in 2019, reaching a seven-year peak of 45,754 cases. All of the increase in insolvencies in the 2018 to 2019 period was for proposals to restructure debt rather than bankruptcies, which recorded modest declines.[2]

The increase in insolvencies in 2018 and 2019 can mostly be attributed to the impact of rising interest rates on the financial position of households, which had accumulated a record amount of debt relative to income. From 2017 to 2019, the Bank of Canada raised its policy rate by 125 basis points to the highest point since the 2008-09 recession. At the same time, borrowing costs for households and businesses rose as lenders generally paralleled the Bank’s interest rate moves. Higher interest rates contributed to rising debt service costs[3] which reached 8.3 per cent of disposable income in 2019, up from 7.0 per cent in 2015 and the highest since 2008.

Figure 1: Rising interest rates created financial challenges for households prior to the pandemic

Source: Statistics Canada, Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy and FAO.

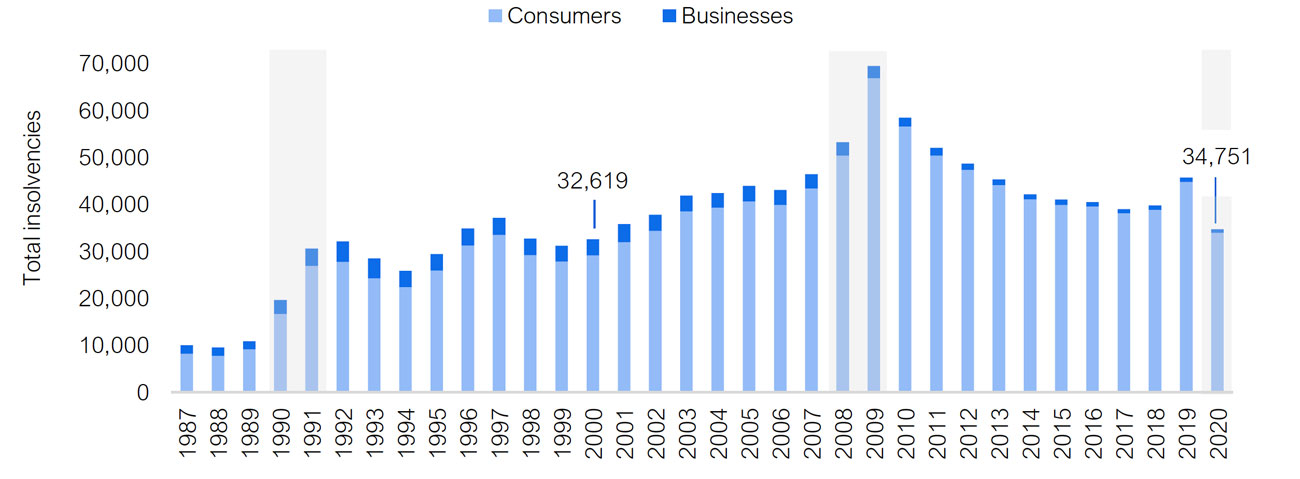

Insolvencies in Ontario declined sharply in 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic and government mandated restrictions to contain the virus had significant negative impacts on Ontario’s economy, resulting in a record drop in real GDP in 2020 and creating financial hardship for consumers and businesses. The province experienced a record decline in employment of 355,300 (or -4.8 per cent) in 2020,[4] which contributed to a 1.3 per cent decrease in labour income. In the business sector, the pandemic-related shutdowns caused a significant slump in sales[5] and corporate profits declined by 9.9 per cent.[6]

However, despite the economic damage the pandemic caused to household and business finances, insolvencies in Ontario declined sharply in 2020. Total consumer and business insolvencies dropped by a record[7] 24.0 per cent in 2020, falling to 34,751 which marked the lowest annual level since 2000. Among consumers, insolvencies dropped by 24.2 per cent in 2020 to 33,992, while cases filed by businesses declined 15.9 per cent to 759.

Figure 2: Annual insolvencies in Ontario in 2020 reached the lowest level in two decades

Source: Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy.

Shaded areas represent recessions.

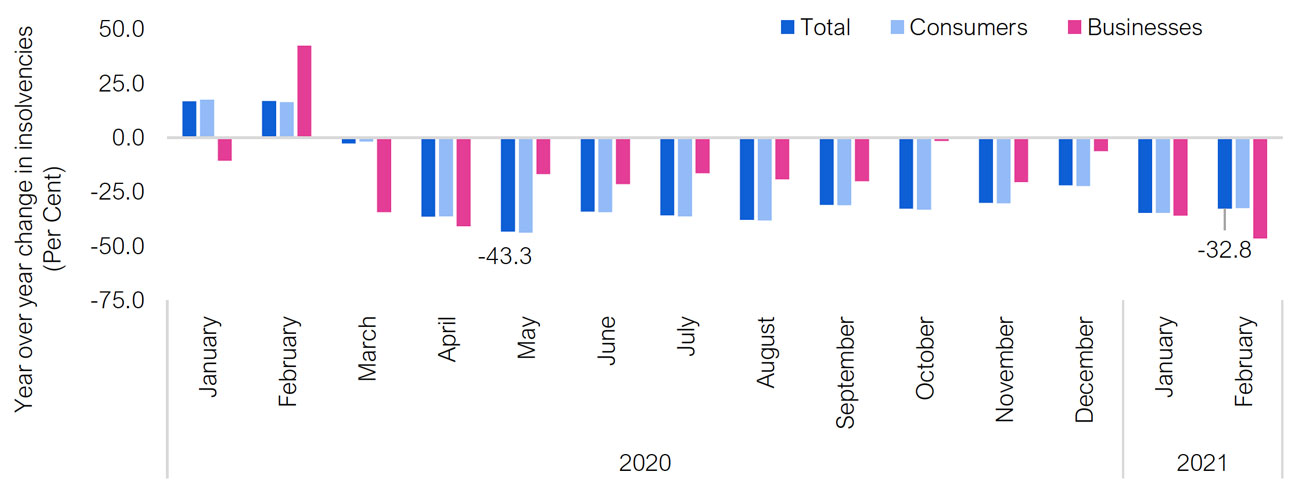

The sharp decline in insolvencies in 2020 occurred as the COVID-19 pandemic progressed. Prior to the pandemic, total insolvencies were 16.8 per cent higher in the January-February 2020 period compared to a year earlier. However, as the number of COVID-19 cases increased and the government enacted restrictions, insolvencies began to decline by record amounts and by May were 43.3 per cent below year-earlier levels. Even though insolvencies began to increase in the summer of 2020, they were still 32.8 per cent lower in February 2021 compared to a year earlier.

Figure 3: Insolvencies in Ontario declined dramatically as the pandemic progressed

Source: Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy.

Temporary factors contributed to the decline in insolvencies in 2020

Source: Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy.

Source: Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy.

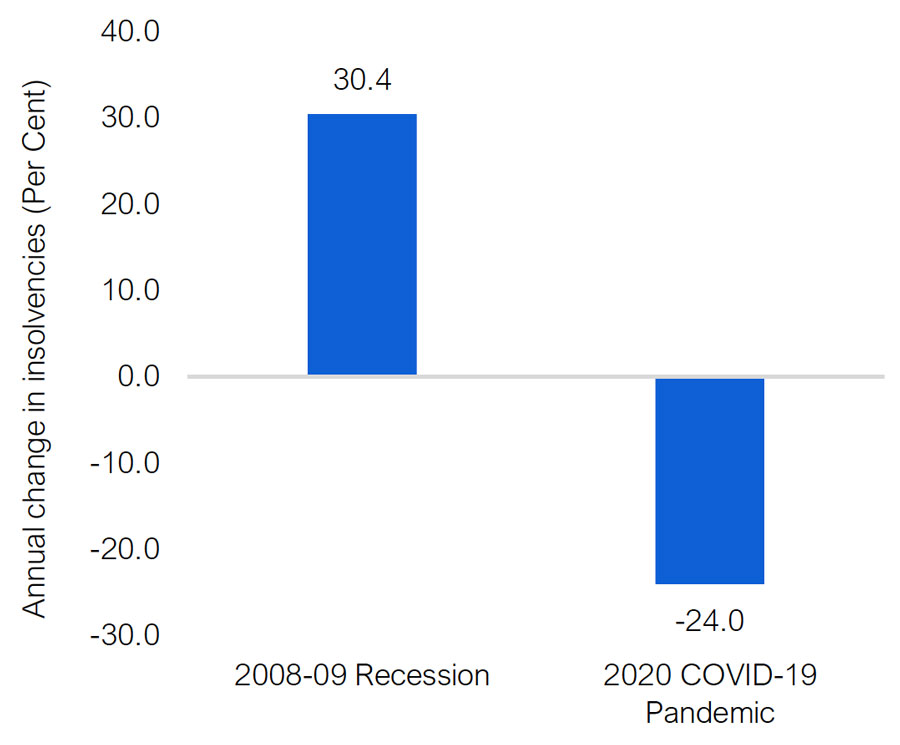

Historically, insolvencies increase during recessions as financial problems emerge and deepen, making it difficult for households and businesses to meet debt obligations. During the previous recession, total insolvencies in Ontario increased by 30.4 per cent in 2009. The significant 24.0 per cent drop in insolvencies in 2020 is exceptional among recessionary periods and reflects a number of unique temporary factors related to the pandemic.

In March 2020, the Bank of Canada rapidly lowered its policy interest rate by 1.5 percentage points in response to the impending economic downturn, helping reduce debt payments faced by consumers. As of the fourth quarter of 2020, lower interest rates helped reduce average consumer monthly debt payments by 6.2 per cent for those without a mortgage and by 3.4 per cent for mortgage holders compared to a year earlier.[8]

Since the pandemic outbreak began, government lockdown restrictions resulted in the shutdown of many in-person services, and temporarily reduced the capacity of Ontario’s courts, affecting the timing of legal proceedings. Debt payment deferrals by creditors have also helped lessen the financial strain faced by some households.[9] For example, the proportion of Ontario residential mortgages in arrears was essentially unchanged at 0.1 per cent in 2020.[10] In contrast, this ratio has increased in previous recessions – from 0.2 per cent in 1990 to 0.5 per cent in 1991, and from 0.3 per cent in 2008 to 0.4 per cent in 2009.

Although labour income and corporate profits declined in 2020, federal government measures such as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) and Canada Emergency Business Account (CEBA) provided significant financial support to Ontario households and businesses. Among households, disposable income increased by 9.6 per cent in 2020, reflecting significant support from the federal government. Without this support, household incomes would have declined by an estimated 1.6 per cent in 2020. Based on national data, household disposable income has increased at a faster pace for lower-income and younger households, even though they recorded the sharpest losses in labour income.[11]

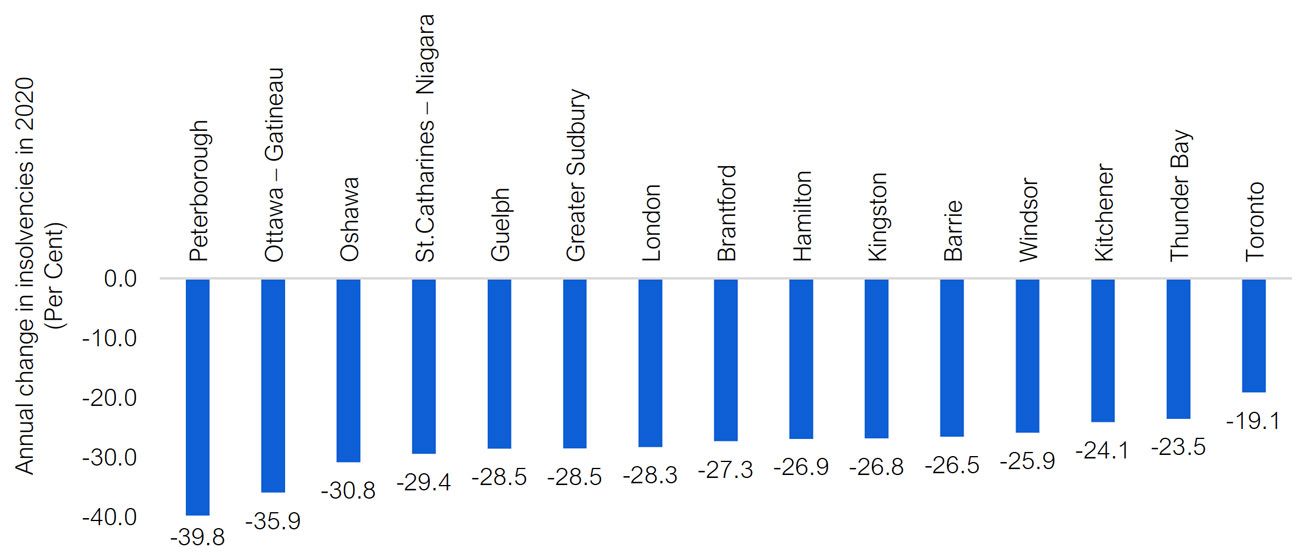

All major cities experienced lower insolvencies

Insolvencies declined in all Ontario census metropolitan areas (CMAs[12]) in 2020. Peterborough recorded the largest decline in insolvencies (-39.8 per cent), while Toronto experienced the smallest decrease (-19.1 per cent). On a per capita basis, Peterborough had the lowest incidence of total insolvencies (0.19 per cent) in 2020, while Greater Sudbury had the highest (0.40 per cent).

Figure 5: Annual total insolvencies declined in all major cities in 2020

Source: Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy.

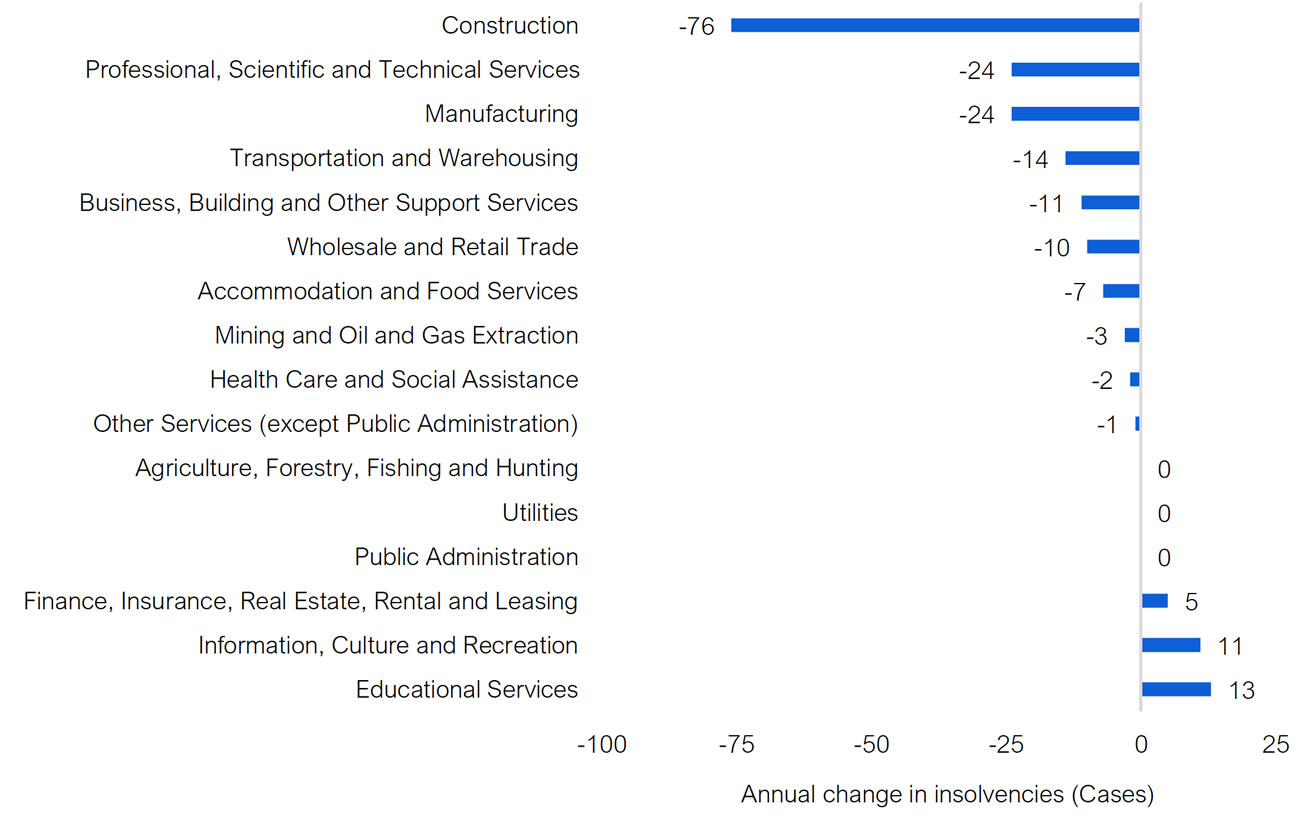

Not all industries saw lower insolvencies

Insolvencies declined in most industries in 2020, led by construction (-76 cases), professional, scientific and technical services (-24), and manufacturing (-24). The three industries hardest hit by the pandemic –– transportation and warehousing (-14), wholesale and retail trade (-10), and accommodation and food services (-7) –– all reported fewer insolvencies in 2020.

Insolvencies increased in three industries, specifically educational services (+13 cases), information, culture and recreation (+11), and real estate (+5). Insolvencies were unchanged in public administration, utilities, and agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting.

Figure 6: Insolvencies increased in three industries

Source: Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy.

Insolvencies declined in all provinces in 2020

Total insolvencies declined in all provinces in 2020. At the national level, total insolvencies dropped by 29.5 per cent, with both consumer (-29.7 per cent) and business (-24.3 per cent) lower. The Atlantic provinces generally had the largest declines in insolvencies, with steep drops in Prince Edward Island (-43.6 per cent), Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia (both -42.3 per cent). Manitoba reported the smallest rate of decline of total insolvencies (-19.6 per cent), followed by Alberta (-21.6 per cent) and Ontario (-24.0 per cent). On a per capita basis, British Columbia had the lowest incidence of total insolvencies (0.16 per cent), while New Brunswick had the highest (0.43 per cent).

Figure 7: Total insolvencies declined in all provinces in 2020

Source: Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy.

Looking forward

Given the ongoing economic challenges related to the pandemic, insolvencies could increase in the medium term and will depend in part on the extent and pace at which government income support is phased out. As well, interest rates are expected to rise gradually which will put upward pressure on debt obligations for many Ontario households.

While many businesses that filed for insolvency in 2020 were in vulnerable financial positions prior to the pandemic,[13] the lingering impact of the economic shutdowns could result in increased insolvencies. In the first quarter of 2021, 41.4 per cent of Ontario businesses indicated they were unable to take on additional debt, including accommodation and food services (59.4 per cent), other services[14] (55.9 per cent), arts, entertainment and recreation (54.7 per cent) and construction (52.5 per cent).[15] In the accommodation and food services industry, 30.3 per cent of businesses reported they could continue operating for less than 12 months before considering closing or filing for bankruptcy.[16] The other services (29.7 per cent) and arts, entertainment and recreation (28.6 per cent) sectors were in similar circumstances.

Appendix A: Insolvency Statistics

Insolvency statistics in Canada are collected and published by the Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy (OSB) since 1987 and consists of bankruptcies and proposals filed by consumers and businesses.

Bankruptcies are agreements to surrender assets to creditors. Proposals are offers to enter an agreement to maintain ownership of assets and repay debt to creditors at a reduced rate for a specific length of time.

Data and reports are released by the OSB each month by province and industry, and on a quarterly basis by census metropolitan area (CMA) and economic region (ER). Data on annual insolvency rates and consumer insolvencies by age and sex are released once a year.

About this document

Established by the Financial Accountability Officer Act, 2013, the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) provides independent analysis on the state of the Province’s finances, trends in the provincial economy and related matters important to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario.

Prepared by:

Jay Park (Economist) and Paul Lewis (Chief Economist).

Graphic Descriptions

Total Insolvencies

(Left)

Debt Service Ratio

(Per Cent)

(Right)

2011

52,074

7.65

2012

48,742

7.38

2013

45,354

7.15

2014

42,198

7.21

2015

41,076

6.98

2016

40,551

6.99

2017

39,045

7.12

2018

39,793

7.83

2019

45,754

8.32

Total insolvencies

Consumer insolvencies

Business insolvencies

1987

10,008

8,233

1,775

1988

9,553

7,763

1,790

1989

10,876

9,150

1,726

1990

19,675

16,708

2,967

1991

30,658

26,944

3,714

1992

32,114

27,777

4,337

1993

28,546

24,316

4,230

1994

25,883

22,419

3,464

1995

29,446

25,915

3,531

1996

34,898

31,292

3,606

1997

37,137

33,524

3,613

1998

32,741

29,252

3,489

1999

31,217

27,822

3,395

2000

32,619

29,151

3,468

2001

35,874

32,027

3,847

2002

37,844

34,392

3,452

2003

41,922

38,525

3,397

2004

42,442

39,331

3,111

2005

43,964

40,654

3,310

2006

43,074

39,946

3,128

2007

46,454

43,413

3,041

2008

53,294

50,442

2,852

2009

69,494

66,935

2,559

2010

58,479

56,619

1,860

2011

52,074

50,460

1,614

2012

48,742

47,381

1,361

2013

45,354

44,134

1,220

2014

42,198

41,108

1,090

2015

41,076

39,935

1,141

2016

40,551

39,611

940

2017

39,045

38,167

878

2018

39,793

38,856

937

2019

45,754

44,852

902

2020

34,751

33,992

759

Year over year change in insolvencies (Per Cent)

Year

Month

Total insolvencies

Consumer insolvencies

Business insolvencies

2020

January

16.8

17.5

-10.7

February

16.8

16.4

42.4

March

-2.6

-1.8

-34.4

April

-36.4

-36.3

-40.9

May

-43.3

-43.8

-16.9

June

-34.1

-34.3

-21.4

July

-35.9

-36.3

-16.5

August

-37.9

-38.2

-19.1

September

-31.0

-31.2

-20.0

October

-32.7

-33.2

-1.5

November

-30.1

-30.3

-20.5

December

-22.0

-22.3

-6.3

2021

January

-34.6

-34.6

-36.0

February

-32.8

-32.5

-46.4

2008-09 Recession

2020 COVID-19 Pandemic

Annual change in insolvencies (Per Cent)

30.4

-24.0

Census Metropolitan Area

Annual change in insolvencies in 2020 (Per Cent)

Peterborough

-39.8

Ottawa – Gatineau

-35.9

Oshawa

-30.8

St.Catharines – Niagara

-29.4

Guelph

-28.5

Greater Sudbury

-28.5

London

-28.3

Brantford

-27.3

Hamilton

-26.9

Kingston

-26.8

Barrie

-26.5

Windsor

-25.9

Kitchener

-24.1

Thunder Bay

-23.5

Toronto

-19.1

Industry

Annual change in insolvencies (Cases)

Educational Services

13

Information, Culture and Recreation

11

Finance, Insurance, Real Estate, Rental and Leasing

5

Public Administration

0

Utilities

0

Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting

0

Other Services (except Public Administration)

-1

Health Care and Social Assistance

-2

Mining and Oil and Gas Extraction

-3

Accommodation and Food Services

-7

Wholesale and Retail Trade

-10

Business, building and other support services

-11

Transportation and Warehousing

-14

Manufacturing

-24

Professional, Scientific and Technical Services

-24

Construction

-76

Province

Annual change in insolvencies (Per Cent)

BC

-26.0

AB

-21.6

SK

-24.4

MB

-19.6

ON

-24.0

QC

-37.1

NB

-30.8

NS

-42.3

PE

-43.6

NL

-42.3

Canada

-29.5

Footnotes

[1] Insolvency is the state of being unable to pay back debt. Insolvencies consist of bankruptcies, which is an agreement to surrender assets to creditors, and proposals to enter an agreement to maintain ownership of assets and repay debt to creditors at a reduced rate for a specific length of time. Statistics on insolvency cases in Canada are published by the Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy. See Appendix A for a description of insolvency statistics.

[2] Consumers make up a large majority of insolvencies at over 90 per cent, and businesses account for the rest.

[3] Debt service ratio is the proportion of household disposable income required to pay interest on debt.

[4] For more information on the impact of the pandemic on Ontario’s labour market, see the FAO’s report on Ontario’s Labour Market in 2020.

[5] In 2020, Ontario retail sales declined by 3.5 per cent and manufacturing sales fell 12.1 per cent.

[6] Measured by the Net Operating Surplus of Corporations.

[7] Based on data covering the 1987 to 2020 period.

[8] Mortgage and Consumer Credit Trends Data, published by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. Data is for Canada.

[9] For details on debt deferrals, see the Bank of Canada’s report Debt-Relief Programs and Money Left on the Table: Evidence from Canada's Response to COVID-19.

[10] Statistics on mortgages in arrears in Canada, Canadian Bankers’ Association.

[11] Household economic well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic, experimental estimates, first quarter to third quarter of 2020, Statistics Canada.

[12] Statistics Canada defines a census metropolitan area (CMA) as a large population centre together with adjacent fringe and rural areas that have a high degree of social and economic integration with the centres. A CMA must have a population of at least 100,000 of which 50,000 or more must live in the urban core.

[13] Study: The impact of the pandemic on the solvency of corporations, third quarter 2020, Statistics Canada, January 2020.

[14] Other services include repair and maintenance; personal and laundry services; religious, grant-making, civic and professional services; and private household services.

[15] Table 33-10-0322-01: Ability of the business or organization to take on more debt, by business characteristics, Statistics Canada.

[16] Table: 33-10-0330-01: Length of time businesses or organizations expect to continue to operate at current level of revenue and expenditures, by business characteristics, Statistics Canada.